Lynn How

Lynn is the Editor at Teacher Toolkit. With 20 years of primary teaching and SLT experience, she has been an Assistant Head, Lead Mentor for ITT and SENCO. She loves to write and also has her own SEMH and staff mental health blog: www.positiveyoungmind.com. Lynn…

Read more about Lynn How

Are current school wellbeing practices effective?

All too often, wellbeing policies and practices in school have been a surface value, box-ticking exercise. This research sets out to deepen understanding of how to create effective wellbeing environments, as well as highlight the currently less effective practice in some international settings

Aims

This article provides a critique of contemporary understandings and practices related to well-being in education.

Methodology

This article analyses conceptual and policy frameworks related to well-being in the Canadian province of Ontario. It includes findings from 222 interviews with educators in terms of their understanding of well-being. There are also references to the research and development work in the U.S., Germany, and Norway.

Findings

Wellbeing in educational policies and settings are an important step forward in educational change …

… but this progress is in danger of being reified through simplistic understandings of life satisfaction and other frameworks that evade the complexity of human development.

Further noteworthy areas

- The study mentions comparisons between global education systems.

- It gives reference to the opinion that test led systems narrow curricula.

- The study questions how the notion of wellbeing is being defined in official documents. Are systems trying to balance out the negative aspects of raising academic achievement?

- Questions are raised regarding the focus on more positive aspects of wellbeing without acknowledging other emotions and how to navigate them.

- The pandemic added the extra dimension of whether traditional methods of education are of value when in the context of meaning and purpose.

- We need to look beyond wellbeing to support pupil aspirations and resilience.

In 2016, the OECD published its first study of child well-being to accompany the publication of the usual PISA test results. These showed that high-achieving Korea and Japan ranked near the bottom in child well-being, as did the four jurisdictions in the People’s Republic of China that were assessed. Norway, firmly in the middle of the PISA academic rankings, was at the top. Child well-being was only average in the highly touted reference societies of Canada and Singapore.

Ontario school findings

- Within the study of Ontario schools, wellbeing programs such as yoga were popular but programs focused on pupils needing to fit into traditional rules and routines of school life. Whereas more energetic wellbeing concepts such as play, were not conceptualised in the Canadian structure as part of wellbeing.

- In Ontario, the wellbeing agenda appeared to be mainly supporting the management of stress caused by exams.

- The reader is encouraged to think beyond well-being and imagine an education for wholeness that welcomes in dimensions of life such as community engagement, physical education, and the creative arts into Ontario schools.

Well-being was not being developed to promote critical ways of thinking about the world, or to impart to the young moral lessons that could help with their overall socialization.

Bringing purpose into schools

The study states this can be improved by:

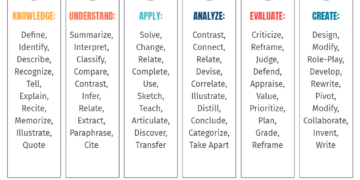

- More ‘deep learning’ whereby pupils are able to have some choice over what they are learning which pupils will find more meaningful.

- Enhanced teaching whereby teachers are able to open up dialogue about the purpose of given activities. Many teachers evaded pupil questions, thus missing opportunities.

- Small scale purposeful interventions for particular pupils with a councillor to provide a role model and support with learning.

Finally, another way to bring purpose into schools would be by transforming entire schools and systems so that all students have opportunities for continual conversations with adults about what activities they could find meaningful and how best to realise them.

Conclusions

- Wholeness: Wholeness in this regard refers to the dynamic unfolding of the individual over time. This includes the ability of the self to practice mindful detachment, and to view oneself from other points of view, including those that are critical. Such a disposition should not be viewed as one tangential part of an education, but rather as an essential component of one’s moral formation over time.

- Incorporation of wholeness: This can be done in small steps by changing our pedagogies and revising our curricula. More ambitiously, it is time to rethink the bureaucratic structures of schooling that too often lead to dehumanizing situations in which students are not encouraged to explore the purposes which they would like to give to their lives.

- Educator influence: Educators frequently underestimate their power and influence, deferring to the authority of others even on matters in which they know better.

- Rethink: Our schools need a fresh burst of humanistic education. This must value individuals in their quest for well-being but also encourage them to be their best whole selves, with their freely chosen inspirational purposes guiding their lives.

By bringing issues of wholeness and purpose back into the centre of contemporary school improvement deliberations, it is possible to develop models of education that go deeper and are more rewarding than has been attainable in the recent past.