Her doctor prescribed some medications, but Yvonne, 22 at the time, continued to lose perspective. Maybe the voices weren’t just her mind playing tricks on her? Maybe they were real? That’s when the aliens arrived. She heard the loud, screeching sound of their ship hovering outside her window at night.

“We need to remove you from this planet,” the aliens told Yvonne. Then they spoke to each other in their own gargled alien language that she couldn’t understand.

Yvonne had no doubt this was real. And when God started talking to her a few weeks later, that was real, too. He told her she was going to be the next Jesus and he was going to give her instructions on how to save the world. At first, this made Yvonne feel great. God had chosen her. But then she got scared, overwhelmed by the responsibility. What if she couldn’t fulfill what God wanted for her?

“He’s going to send me to hell and I’m a terrible person,” Yvonne said.

Yvonne’s mom convinced her to check herself into the hospital. But it was almost six months after she left the hospital that she got an accurate diagnosis: schizoaffective disorder — roughly, schizophrenia with bouts of mania or depression. And for another six months after that, she sat on her parents’ couch, unable to read, unable to go to school, waiting for a spot to open up in a treatment program.

“My life wasn’t my own,” said Yvonne, who asked that we use a family name to protect her mental health history. “It was up to these voices because they told me what to do. They wouldn’t go away and I couldn’t do anything with them. So they ruled my life.”

Yvonne is one of 100,000 young adults or adolescents who have a psychotic episode every year in the U.S. For most of them, it takes a year and a half to get into meaningful treatment, if they ever do at all. Treatment programs recommended by the National Institute of Mental Health as the gold standard of care for early psychosis rarely have enough slots available for the people who need them, and health insurance companies typically refuse to cover the full cost of these programs, even when they are available.

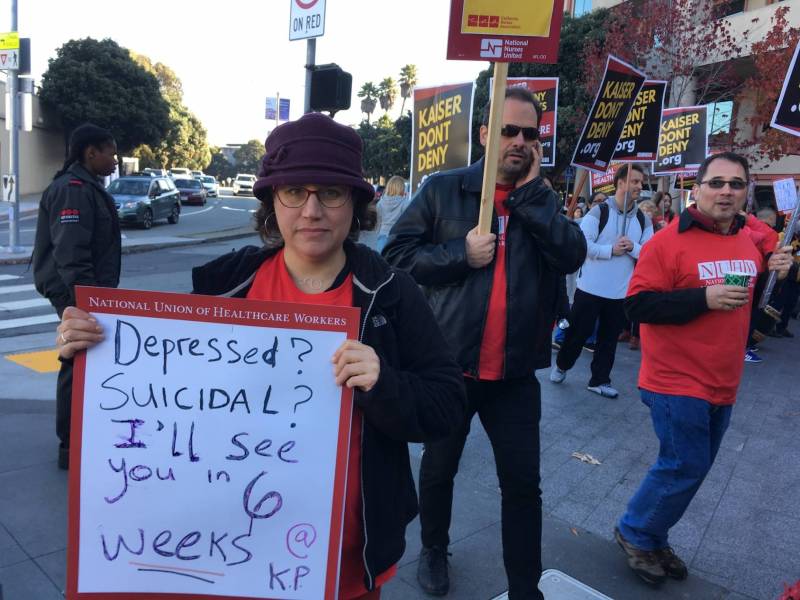

Mental health clinicians at Kaiser Permanente went on strike in December 2018 and 2019 over long patient wait times. (April Dembosky/KQED)

Mental health clinicians at Kaiser Permanente went on strike in December 2018 and 2019 over long patient wait times. (April Dembosky/KQED)

Instead, many young people like Yvonne inch through the country’s fragmented mental health care system, struggling to find a clinician with adequate training in psychosis. Yvonne waited up to six weeks between therapy appointments at Kaiser Permanente, and said she made little progress with a clinician who always seemed to change the subject when Yvonne wanted to talk about her voices. “She would skip over it and talk about my anxiety instead,” Yvonne said.

Eventually, Kaiser agreed to pay for Yvonne to go to the UCSF Path Program for Early Psychosis, a two-year outpatient treatment program designed specifically for young people in the earliest stages of psychotic illness. The clinic is one of about 50 in California and 340 across the country that began operating in the mid-2000s. Right away, Yvonne knew this would be different. In her first session, Yvonne’s therapist had her set goals for what she wanted to achieve.

“No one had ever asked me what my goals for treatment were,” Yvonne said.

A revolutionary idea for treating schizophrenia

Back in the ’80s and ’90s, doctors didn’t really know what to do with schizophrenia, and they didn’t have many options. They prescribed high doses of antipsychotic medications that sedated people into zombie-like depths. They advised patients to give up on any career ambitions and sign up for disability payments instead. Even today, some doctors still see schizophrenia as a lost cause.

“There’s a real failure to appreciate how much potential there is to manage the illness and symptoms,” said Dr. Daniel Mathalon, a psychiatrist at UCSF’s early psychosis program.

Around the turn of the century, a new generation of doctors started thinking, What if we ask patients what they want and actually work with them toward full recovery? “It’s not just about stabilizing you clinically. It’s about making sure we don’t lose track of your future,” said Tara Niendam, a child psychologist who runs the early psychosis clinic at UC Davis. “You should be in college. You should be living on your own.”

With other conditions like diabetes or cancer, the sooner people get into care, the better they do. The same is true of psychotic illness. Upwards of 80 studies from early psychosis clinics show that patients see a greater reduction of symptoms, like voices or delusions, and a greater improvement in functioning at school, at work and in their social lives, compared to people who get treatment as usual.

There are a few reasons why earlier treatment is more effective, Niendam said. People respond more quickly to medication and at a lower dose, so they have fewer side effects that make them want to stop taking them. Families are more involved and more supportive, and patients themselves are more curious about their psychotic experiences. “They come out of it and they’re like, ‘Whoa! What was that?’” Niendam said. “Folks are still in that questioning phase.”

When someone is deep in psychosis, their beliefs are rigid, intractable. They might not see themselves as being sick. But if they get help earlier, Niendam said, they’re more likely to engage in treatment.

Clinical psychologist Tara Niendam speaks with a colleague at the UC Davis Behavioral Health Center in Sacramento on Feb. 7, 2023. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Clinical psychologist Tara Niendam speaks with a colleague at the UC Davis Behavioral Health Center in Sacramento on Feb. 7, 2023. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

For Yvonne, even though she believed the alien ship outside her window was real, her doctors at UCSF started her on a new medication that shook that belief loose. Her new therapist then used targeted cognitive behavioral techniques that helped Yvonne challenge those beliefs further.

“So for example, I’d have a thought: ‘Aliens are going to abduct me,’” she said. “So then we do ‘evidence for’ that thought and ‘evidence against’ that thought.”

First, she made a list of all the evidence she had that the alien abduction plan was real: I hear the aliens. They’re talking to me. I hear their ship.

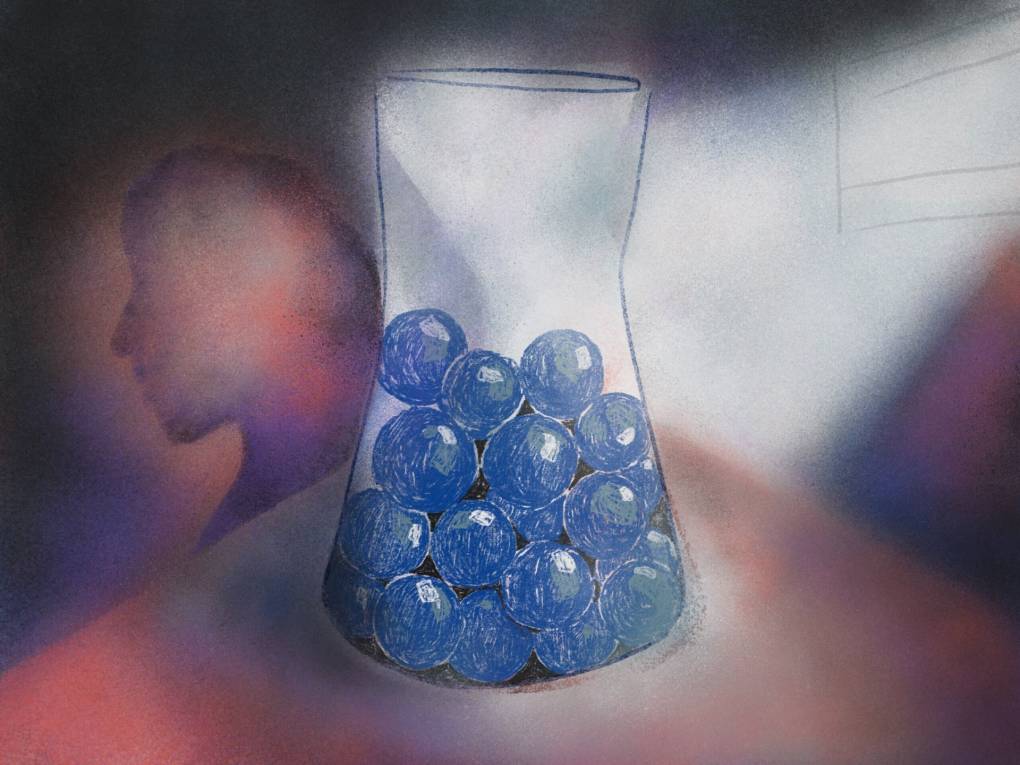

Then she had to list the evidence that they weren’t real. For this, the therapist had Yvonne set up a jar in her bedroom. Every morning that she woke up and had not been abducted, she would put a blue marble in the jar. If she had been abducted, she was supposed to put a white marble in the jar.

“And I had all blue marbles,” Yvonne said. “So that’s evidence against ‘they’re going to get me,’ cause they haven’t yet.”

To get control over the voices in her head, Yvonne learned to talk back to them. She would sit in the therapist’s office, in the chair on the right side of the room, and pretend to be her voices, telling her to go back to bed or not to go outside. “It’s dangerous,” she’d say.

Then Yvonne would go sit in the chair on the left side of the room and practice her response.

“Thank you, voices, for wanting to protect me and watch out for me,” she’d say back. “But I’m going to get up and be brave and go out into the world today.”

It took a while to get the hang of it, maybe a year, but when she did, Yvonne was able to go back to school. When the voices would start yelling at her while she was in class, calling her dumb, she was ready.

(Illustration by Anna Vignet/KQED)

(Illustration by Anna Vignet/KQED)

“I’d be like, ‘You know what? I really don’t appreciate the way you talk to me. Let’s talk after class, let’s talk at 2 p.m.,’” she told them.

The voices wouldn’t go away completely, but they would fade into the background, enough where Yvonne could finish class or read a book or do her homework. “I just started to feel more in control,” said Yvonne, now 27.

She graduated college last spring, summa cum laude, and she’s now working a full-time job. She’s about to move into her own place. She keeps up with her broad circle of friends, going to shows in the city or having bonfires on the beach. If she thinks she hears a voice or an alien, she does a literal reality check. “Oh, did you hear that?” she’ll ask a friend or her mom. And if they don’t, she tells herself, “Okay, that’s just a voice.”

But mostly, Yvonne doesn’t like talking about her illness with her friends. She’d rather talk about the Kardashians instead.

“I just like to be normal when I’m with them,” she said.

Independent, career-oriented people

Even though the skills Yvonne learned from therapy at UCSF were a revelation, there was actually a whole other dimension of care that she never got. That’s because UCSF’s program only accepts private insurance, and private health insurers only cover about half of the services of early psychosis treatment.

People who get care under government health coverage, like Medi-Cal, can enroll in programs like the Felton Institute’s, which offer not just specialized therapy, like Yvonne got, but a full array of social support, as well. At Felton’s five clinic locations, they believe it takes a full team of specialists who all talk to each other, who are all looking out for every aspect of a young person’s life.

That includes specialists like Monet Burpee, an education and employment coach. On a typical workday, she’ll drive her clients to the local mall or downtown shopping district, charting their path according to the “Help Wanted” signs. Together, they’ll chat with store managers about open positions, then sit down and fill out the applications.

Burpee says helping her clients who have psychosis find work is about more than landing a job; it’s about helping them see themselves differently, as independent, career-oriented people, rather than permanent patients receiving government wage assistance.

“If you work, you’re going to notice a huge improvement in your self-esteem,” she tells them. “It has better long-term, positive results versus you just sitting around on SSI.”

Monet Burpee (right) talks to the manager of a restaurant in Redwood City on one of her job-scouting expeditions in July 2022. (April Dembosky/KQED)

Monet Burpee (right) talks to the manager of a restaurant in Redwood City on one of her job-scouting expeditions in July 2022. (April Dembosky/KQED)

This is what she said to one of her clients, Sandy, after she had her first psychotic episode. Sandy was taking new medications that made her really sleepy, and she was struggling to get motivated.

“Since I didn’t really have anything to do, I would just take superlong naps during the day,” said Sandy, now 20, who asked that we call her by a family name so her health history doesn’t disrupt her career path.

For her, psychosis hit when she was working her first job after high school, at a fast-food restaurant making burgers. Her co-workers were chatting over the fryer one day when Sandy got this weird feeling, that somehow they knew what she was thinking. It was like her co-workers could read her mind and were discussing her thoughts with each other.

“I was like, are they talking about burgers or are they talking about me?” Sandy said.

There was one co-worker in particular, a guy she had a crush on, that she was pretty sure was watching her — even following her around. If she was walking down the street, or hanging out in the park, she saw him. Her mom remembers Sandy wanted to sleep with the lights on, repeatedly asking her, “Mom, is someone here?”