The most frequently burned watersheds in the Sierra Nevada (likely because they are remote and hard to access) have something in common: The fish seem to thrive with the fire. That was a striking finding from a study commissioned by Congress involving several research teams in the 1990s to evaluate the health of the Sierra Nevada.

Carl Skinner, retired research geographer with the U.S. Forest Service, was part of that research group.

“What was interesting is that there were aquatic biologists that were studying these creeks also, independent of us,” he said, referring to Deer Creek and Mill Creek, “and they determined that these watersheds contained an intact native fish and amphibian fauna.”

In other words, the life in these streams were doing great. They were operating naturally, as they would have prior to the colonization of California by Europeans and the rapid development of the state.

A 2005 study of fish and fire in Idaho by Bureau of Land Management researcher Timothy Burton found that “even in the most severely impacted streams, habitat conditions and trout populations improved dramatically within 5-10 years.”

Floods that followed fires “rejuvenated stream habits” by delivering fine sediments and large amounts of gravel, cobble, woody debris and nutrients that resulted in “higher fish productivities than before the fire,” the study found.

Severe fire prompts a devastating fish kill

The link between fish and fire is not always beneficial.

Severe fires, especially with the big debris flows that can follow when rains come, can kill large numbers of fish. Last August the McKinney Fire prompted a devastating fish kill along 50 miles of the Klamath River.

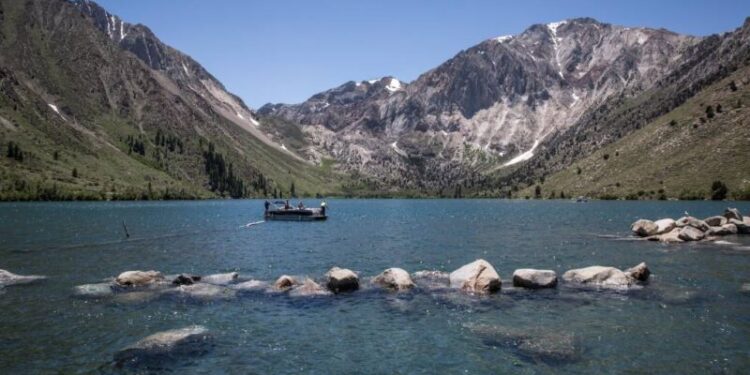

The Klamath River runs brown with mud after flash floods hit the McKinney Fire in the Klamath National Forest near Yreka. (David McNew/AFP via Getty Images)

The Klamath River runs brown with mud after flash floods hit the McKinney Fire in the Klamath National Forest near Yreka. (David McNew/AFP via Getty Images)

“It was kind of a combo of worst-case scenarios,” said Toz Soto, fisheries program manager for the Karuk Tribe. “I’ve lived in the Klamath my entire life, and I’ve seen a lot of fires and I’ve seen a lot of debris flows and flood effects and things of this sort. But we’ve never experienced anything quite like this.”

The McKinney Fire, which took the lives of four people, broke out in steep territory in a dry area of the mid-Klamath mountains and burned fast and hot, driven by winds. Within days, isolated heavy rains dumped over the burn scar, releasing enormous amounts of mud and rock into the river. The flow of the Klamath River, as measured by a stream gauge, doubled within a matter of hours.

Soto said he first noticed a change in the sound of the river. “The rapids weren’t making any noise — they were gurgling, but they weren’t roaring,” he said. “The white water wasn’t white. Things were different.”

The extremely muddy, “eerily quiet” water saw big drops in its oxygen content, “pretty much down to zero,” he said.

When it’s that low, Soto said, “you might as well just throw the fish up on the bank.”

Soto worries that as climate change accelerates the intensity of wildfires and rainstorms, these sorts of events will become more common.

Yurok tribe member Thomas Willson of Weitchpec fishes on the Klamath River within Yurok tribal lands in this 2008 photograph. (Michael Macor/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

Yurok tribe member Thomas Willson of Weitchpec fishes on the Klamath River within Yurok tribal lands in this 2008 photograph. (Michael Macor/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

But there are solutions. Traditional Indigenous knowledge points to the value of using fire to stave off the worst wildfires and to promote health in the forests and aquatic ecosystems.

“If we want healthy water for salmon or for drinking or for planting fruits and vegetables, we need to take care of our forest,” said Margo Robbins, Yurok tribal member and executive director of the Cultural Fire Management Council, “and the most efficient, most cost-effective way to take care of the forest is with fire.”

“It’s critical for us as Native people to restore those things back into a healthy state,” she said.

And, she stressed, everyone has a role: “It’s critical for non-Native people to also take their part in restoring the land to a healthy state, too.”