As a retired elementary educator, I’ve seen firsthand how foundational reading skills shape the trajectory of a child’s academic success and overall confidence. I had the privilege of working with a former student we will call Ethan. Ethan was a bright and curious child who struggled deeply in reading. He stumbled over very simple words, had no confidence, and avoided reading tasks due to embarrassment. His frustration was evident and his confidence quickly unraveled. I focused on systematic, explicit phonemic awareness and phonics instruction. We practiced structured literacy intervention and fluency building activities. By mid-year Ethan realized he was reading and was full of excitement. By the end of the year, Ethan had closed the gap significantly and was almost at grade level. This was indeed life changing for Ethan.

The term “science of reading” has gained momentum recently but is far from a passing trend. It represents decades of research across cognitive psychology, linguistics, and education, shedding light on how children learn to read and, just as importantly, how they don’t. For teachers, understanding the science of reading isn’t just about adopting new strategies; it’s about rethinking how we approach literacy instruction to ensure all students have the tools they need to thrive.

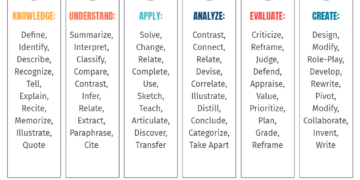

The science of reading refers to evidence-based research that explains how the brain learns to read. Unlike speaking, which is innate, reading is not a natural process. It requires explicit instruction because it involves connecting sounds (phonemes) to written symbols (graphemes) and integrating this with language comprehension. The research emphasizes the importance of five critical components of reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

This approach is supported by decades of studies, including groundbreaking work on how the brain processes written language. Neuroimaging studies reveal that learning to read rewires the brain, activating specific regions like the visual word form area. This evidence underscores why systematic, explicit instruction is vital—particularly for struggling readers or those with learning disabilities like dyslexia. Structured literacy approaches such as Orton-Gillingham and Lindamood-Bell can rewire the brain’s reading pathways. Rewiring brain pathways, improving literacy skills, and helping struggling readers succeed provides clear scientific evidence that reading is a science.

The Teacher’s Perspective

Teachers often wear many hats: instructor, mentor, cheerleader, and problem-solver. When it comes to teaching reading, the stakes are incredibly high. Reading is the gateway skill; without it, accessing other areas of learning becomes nearly impossible. The Science of reading is based on a convergence of evidence, including research of phonemic awareness, phonics, and targeted evidence-based interventions, which can lead to measurable improvements. Brain imaging studies reveal that proficient readers activate the left occipitotemporal region of the brain. The science of reading helps us understand how to help a struggling student better activate this same region of the brain.

Here are a few key takeaways from my time in the classroom and how they connect to the science of reading:

Phonemic Awareness is Essential

One of the most common misconceptions I encountered early in my teaching career was the idea that exposure to books and language-rich environments was enough for all children to learn to read. While these factors are undoubtedly beneficial, they don’t replace the need for explicit phonemic awareness instruction.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds in words. For example, phonemic awareness recognizes that the word “cat” has three sounds: /k/, /a/, and /t/. Many struggling readers lack this foundational skill, making it difficult for them to decode words.

In my classroom, I saw how systematic phonemic awareness activities—such as segmenting, blending, and manipulating sounds—transformed students who initially struggled with reading. It reinforced that teaching phonemic awareness isn’t just a kindergarten activity; it’s a cornerstone of literacy instruction. Phonemic awareness is based on cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and linguistic research, all of which show that the brain must be explicitly trained to recognize and manipulate sounds. Brain imaging studies (Shaywitz, 2003) show that struggling readers have weaker brain activity. Explicit instruction rewires the neural pathways proving that reading is a cognitive skill that follows scientific principles.

Phonics is Non-Negotiable

Explicit phonics instruction often receives pushback, with critics arguing it’s too rigid or uninspiring. However, the science of reading is precise: systematic phonics is critical for helping students understand the relationship between letters and sounds. Without it, many children rely on guesswork or memorization, strategies that eventually fail them when they encounter unfamiliar words.

I recall working with a third grader who struggled to read fluently. The student made remarkable progress after a phonics intervention that included decoding practice and repeated exposure to high-frequency words. Phonics wasn’t a quick fix but provided the scaffolding he needed to build confidence and competence. Explicit phonics instruction helps to rewire the brain and activate the correct region. Reading is a science as it proves that phonics instruction is essential for training the brain to process written language efficiently.

Fluency and Comprehension Go Hand in Hand

Fluency—reading with speed, accuracy, and expression—is often overlooked instead of focusing on comprehension. However, fluency is the bridge between decoding and understanding. A student who reads haltingly will struggle to retain meaning, even if they understand the individual words.

Repeated readings, choral reading, and partner reading were staples in my classroom. These activities built fluency and instilled a sense of enjoyment and collaboration. Fluency practice and discussions about the text helped students connect the mechanics of reading to its ultimate purpose: making meaning. Fluency and comprehension are critical components of the science of reading because they are rooted in cognitive psychology, neurological, and linguistic research. The Simple View of Reading ( Gough &Tunmer, 1986) defines reading as the combination of decoding and language comprehension, which depend on fluency for automatic word retrieval and comprehension for meaning-making.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite its proven effectiveness, the science of reading is not without challenges. Many teachers were trained in outdated methods like whole language or balanced literacy, which often downplayed explicit instruction. Transitioning to a science-based approach requires professional development, resources, and, perhaps most importantly, a mindset shift.

Additionally, schools must address equity. Not all students come to school with the same background knowledge or experiences. For those from disadvantaged backgrounds, the science of reading is even more critical because it provides a structured, equitable approach to literacy instruction.

Conclusion

So yes, the science of reading is truly a science. However, it isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution; it provides a research-based framework that can guide teachers in meeting the diverse needs of their students. As educators, we are responsible for staying informed and adapting our practices based on what the evidence tells us. By embracing the science of reading, we can ensure that every child has the opportunity to become a confident, capable reader—opening the door to a lifetime of learning and discovery.