The city also captures runoff and sewage in three above-ground reservoirs, storing the water until it can be treated and released. The current system can store 11 billion gallons of water and will have the capacity to hold 17.5 billion gallons by 2029.

“It is working, but there is always going to be some storm that will create problems,” said Marcelo Garcia, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “When the tunnels and reservoirs fill up, and you get another storm that takes you basically back to ground zero.”

Today, the city discharges about 10 times annually, about the same as San Francisco. The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago hopes discharges will decrease when the new reservoir is finished.

“The pollution load has drastically decreased,” said Kevin Fitzpatrick, assistant director of engineering for Chicago’s reclamation district. But storms are testing the system, he added, which was designed before the current effects of climate change.

Building Chicago’s infrastructure: Workers construct the Calumet Sag Sewer near 127th Street and the Little Calumet River on July 20, 1921. This vital project helped expand the city’s sewer system, supporting flood control and wastewater management in the growing region. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago)

Building Chicago’s infrastructure: Workers construct the Calumet Sag Sewer near 127th Street and the Little Calumet River on July 20, 1921. This vital project helped expand the city’s sewer system, supporting flood control and wastewater management in the growing region. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago)

“The waterways are cleaner than ever, but we still have flooding,” Fitzpatrick said. “So we realize [the tunnels and reservoirs] aren’t the only solution.” The agency also manages porous parking lots and hundreds of other projects that allow rainwater to infiltrate into the ground.

What can San Francisco learn from Chicago regarding reducing dirty flows? Garcia said tunnels are an “obvious thing to do,” but it is important to remember that Chicago has many times the open space and can store 16 times more water than San Francisco.

The SFPUC said digging tunnels would significantly raise water bills for San Franciscans. In a fact sheet, the agency wrote the 7-by-7 mile-wide city would need 13 miles of tunnels 24 feet in diameter to capture overflows just on the city’s bayside each year but noted it still wouldn’t prevent discharges “in the biggest storms.”

New York — ‘An all-the-above strategy’

In 2005, the federal government cited New York City for violating the Clean Water Act because its sewer systems spewed contaminated water into Flushing Bay, Jamaica Bay and tributaries to the East River, Long Island Sound and Outer Harbor. Around 60% of New York City’s sewers are part of a combined system.

Unlike Chicago, which sits on massive amounts of limestone that it was able to dig into, New York City has limited subterranean space, extensive underground infrastructure and a high water table.

A living landscape: The green roof at Greenpoint Public Library in Brooklyn, New York, on March 7, 2025. Completed in 2020 as part of the library’s Environmental Education Center, the space features soil beds for horticultural programs, solar panels for renewable energy and permeable paving to manage rainwater sustainably. (Jack Beal for KQED)

A living landscape: The green roof at Greenpoint Public Library in Brooklyn, New York, on March 7, 2025. Completed in 2020 as part of the library’s Environmental Education Center, the space features soil beds for horticultural programs, solar panels for renewable energy and permeable paving to manage rainwater sustainably. (Jack Beal for KQED)

The Big Apple has instead invested in more than 13,000 rain gardens, green roofs, permeable pavement and other infrastructure projects.

“New York City is not the first city to use green infrastructure, but it is the first city to broadly implement it specifically for this purpose of combined sewer overflow management,” said Bernice Rosenzweig, professor of environmental science at Sarah Lawrence College.

While New York still grapples with reducing its discharges, Rosenzweig thinks San Francisco can learn a lot from it.

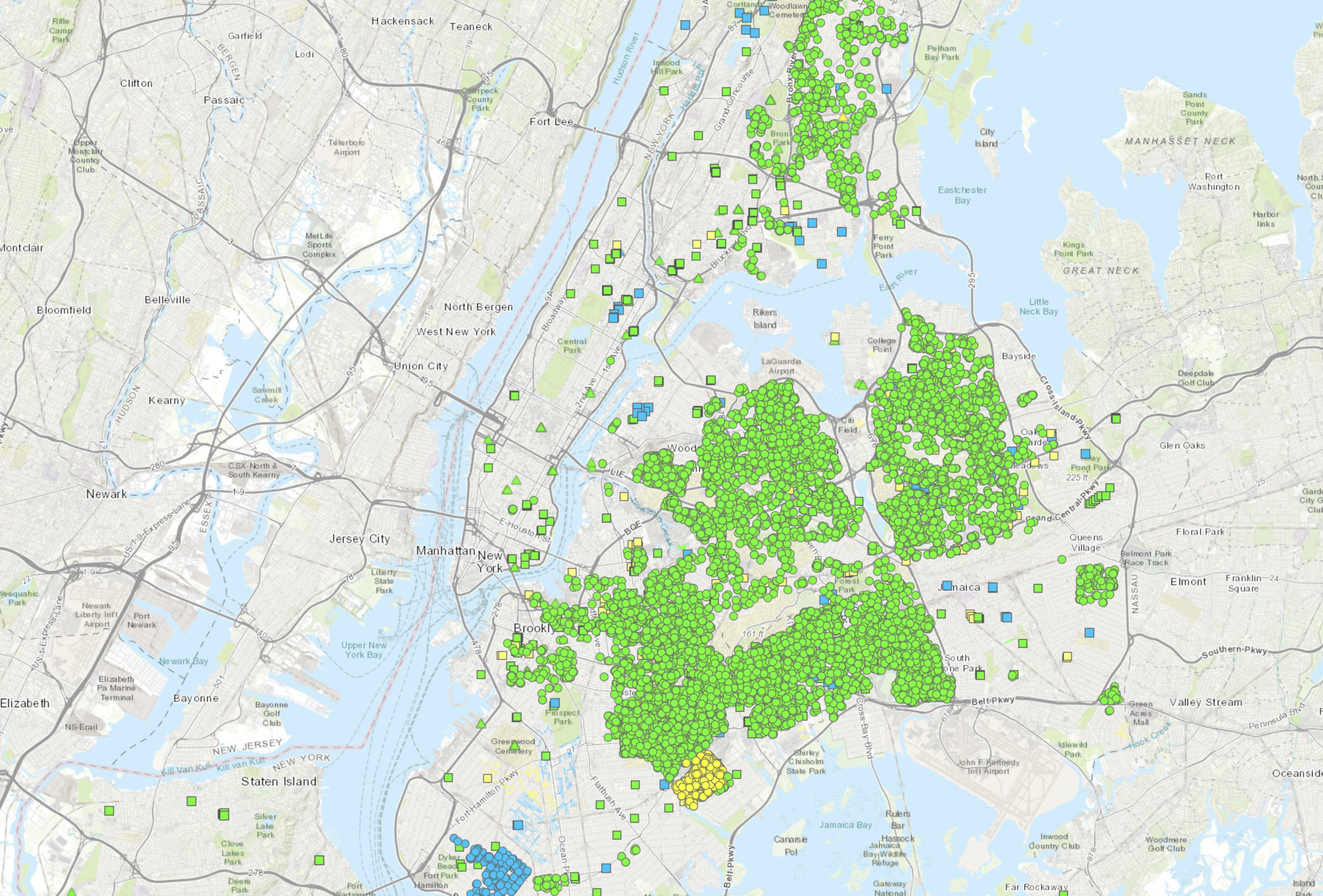

Mapping sustainability: The Green Infrastructure Program map, created by New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection, offers an interactive tool for users to explore green infrastructure projects across the city’s five boroughs, highlighting efforts to manage stormwater and promote environmental resilience. (Courtesy of New York City Department of Environmental Protection)

Mapping sustainability: The Green Infrastructure Program map, created by New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection, offers an interactive tool for users to explore green infrastructure projects across the city’s five boroughs, highlighting efforts to manage stormwater and promote environmental resilience. (Courtesy of New York City Department of Environmental Protection)

“New York City and San Francisco have a lot of similarities,” Rosenzweig said — even though New York’s population is more than 10 times bigger. “They’re some of the densest communities in the United States, and they both rely on subterranean infrastructure.”

Building green infrastructure has the effect of punching “holes” in the hard concrete landscape to “create sponges” so rainwater can be absorbed into the ground, said Jennifer Cherrier, an earth and environmental sciences professor at City University of New York.

The city isn’t relying solely on green infrastructure; it also has plans that include holding tanks, sewer improvements and marsh restoration.

Nature’s solutions: (Left) A rain garden at Saint Mary’s Park in the Bronx, New York, in March 2025, captures runoff from the recreation center’s roof, gradually releasing it to irrigate the garden while easing the strain on the city’s drainage system. The curb cuts direct water from the pavement into the ground. (Right) Snowdrops bloom in a rain garden beside permeable pavers at the Gil Hodges Community Garden in Brooklyn, New York, in March 2025. This rain garden, paired with permeable pavers, captures and reuses over 285,000 gallons of rainwater annually, promoting sustainable stormwater management. (Jack Beal for KQED)

Nature’s solutions: (Left) A rain garden at Saint Mary’s Park in the Bronx, New York, in March 2025, captures runoff from the recreation center’s roof, gradually releasing it to irrigate the garden while easing the strain on the city’s drainage system. The curb cuts direct water from the pavement into the ground. (Right) Snowdrops bloom in a rain garden beside permeable pavers at the Gil Hodges Community Garden in Brooklyn, New York, in March 2025. This rain garden, paired with permeable pavers, captures and reuses over 285,000 gallons of rainwater annually, promoting sustainable stormwater management. (Jack Beal for KQED)

“Our waters are getting a lot cleaner,” Cherrier said. “We have great white shark nursery grounds showing up again. We have had whales underneath the Brooklyn Bridge.”

Still, the advocacy group Save the Sound estimates that more than 21 billion gallons of raw sewage enter New York City’s coastal waters annually, more than 10 times that of San Francisco.

“We really do need an all-of-the-above strategy, and the strategies that are implemented are going to vary across the city,” Rosenzweig said.

Milwaukee — ‘Every drop of water counts’

At the height of a water quality crisis in the 1970s, Milwaukee poured millions of gallons of sewage and stormwater into Lake Michigan an average of 60 times a year. Kevin Shafer, executive director of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, described the rivers in the region “as big, open sewers.”

However, over time, the city brought down the number of discharges; last year, it had only one.

“The goal was zero, and we had one,” Shafer said. “That’s not good enough.”

Lessons from Chicago’s infrastructure: The McCook Reservoir, stages 1 and 2, part of Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), photographed on May 15, 2023, during excavation. This critical infrastructure project is designed to prevent pollution and manage stormwater, helping to protect the city from flooding and improve water quality. (Courtesy of Dan Wendt/MWRDGC)

Lessons from Chicago’s infrastructure: The McCook Reservoir, stages 1 and 2, part of Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), photographed on May 15, 2023, during excavation. This critical infrastructure project is designed to prevent pollution and manage stormwater, helping to protect the city from flooding and improve water quality. (Courtesy of Dan Wendt/MWRDGC)

Milwaukee applied the strategies pioneered in Chicago, digging miles of deep tunnels. It’s also developed more green infrastructure, like New York, transforming more than 5 square miles of land into a watershed and deploying rain barrels and green roofs to capture billions of gallons of water.

“Tunnels are the backbone of everything we do,” he said.

The agency also sends alerts for residents to reduce water use during storms to “preserve the tunnels for the big events by cutting off the water at the surface.”

A step toward sustainability: A green infrastructure installation at San Francisco State University on Feb. 28, 2025, outside the science building. This basin captures and infiltrates stormwater through a spillway, channeling runoff into a swale that directs water to an outlet drain, enhancing the campus’s resilience to heavy rainfall. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

A step toward sustainability: A green infrastructure installation at San Francisco State University on Feb. 28, 2025, outside the science building. This basin captures and infiltrates stormwater through a spillway, channeling runoff into a swale that directs water to an outlet drain, enhancing the campus’s resilience to heavy rainfall. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

“When we started it, we were laughed at,” Shafer said. “Now we have people actively signing up.”

The SFPUC said San Francisco’s water use is low compared to other cities, and the city has enough capacity to not issue household alerts. “We’re more worried about the rain coming down rather than people flushing their toilets; we can generally handle that,” said Joel Prather, the SFPUC’s assistant general manager for wastewater enterprise.

While Shafer understands San Francisco is geographically different, he thinks the city could learn from Milwaukee’s success at reducing pollution in Lake Michigan.

“I think you have to take this approach that every drop of water counts, no matter where it hits the surface,” he said.