Charlotte Frank, who blazed a career path beginning as a fourth-grade teacher in New York City to become a policymaker codifying ambitious curriculums for millions of students, died on May 26 at her home in Manhattan. She was 93.

The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, her son Harley Frank said.

The daughter of an unschooled Eastern European immigrant, Dr. Frank was recruited in 1980 to oversee curriculum and instruction for the New York City school system by Chancellor Frank J. Macchiarola.

She was credited with bringing new thinking to the teaching of reading and math, helping to modernize sex education and supporting the instruction of evolution by barring science textbooks that taught creationism — all within a historically hidebound Board of Education.

“She developed and created curriculum and instruction that made a difference in learning outcomes while navigating a bureaucracy that was reluctant to change,” said Jerald Posman, a former New York City deputy schools chancellor, in an email.

During her tenure, Ms. Frank argued for universal full-day kindergarten and initiated summer programs to instruct teachers at all levels in how to counter racial prejudice in classrooms.

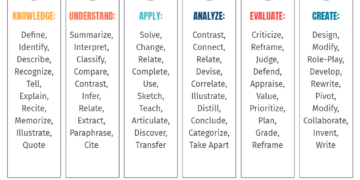

And though she was active in efforts to use math as a tool to inspire cognition, she found that “the ability to solve problems and think clearly transcends problems in mathematics,” she told The New York Times in 1981.

“Thinking skills are common to all the disciplines,” she said, “whether a student is thinking about the causes of inflation in social studies, doing a motion problem in math or trying to understand Shakespeare.”

After nine years as the director of curriculum and instruction, and after confronting what she believed was a glass ceiling for women at the Board of Education, she joined the educational publishing company McGraw Hill in 1988 as senior adviser for research and development. She became senior vice president in 2002 and retired in 2018, when she was 87.

“Charlotte was unique, given that during her period of service, while most teachers were female, few principals and even fewer in leadership roles at school headquarters were women,” said Stanley S. Litow, another former deputy New York City schools chancellor.

In 2000, Ms. Frank was appointed to the New York State Board of Regents, which presides over the State University of New York and the state’s Education Department.

“She was a pioneer in curriculum development, teacher education and professionalizing the career pathways for young educators across the city,” said Merryl H. Tisch, chairwoman of the board of the State University of New York and a former chancellor of the Board of Regents. “Charlotte dedicated her life and her life’s work to the concept of equity long before it became a popular movement.”

Charlotte Kizner was born on April 5, 1929, in the Bronx to Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. Her father, Abraham, worked with a cousin, a glazier, in his auto glass shop in the Bronx. Her mother, Rose (Blivis) Kizner, was a homemaker.

Charlotte grew up in the Parkchester section and graduated from Monroe High School. She earned a bachelor’s degree in business from City College in 1950, a master’s from Hunter College in 1966 and a doctorate in education from New York University in 2000.

She started teaching in 1963, assigned to a fourth-grade class at P.S. 62, across the street from her father’s shop. She later served as district head of testing and then worked in school publishing for the Olivetti company before moving to the Board of Education.

In 1950, she married Sidney Frank; he died in 1988. In 1989, she married Marvin Leffler, who survives her along with three children from her first marriage, Harley and Matthew Frank and Anne Frank-Shapiro; two stepchildren, Bruce Leffler and Nancy Berman; 10 grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Dr. Frank won more than 70 awards during her career as a teacher and administrator and was never reticent about advancing a cause or a curriculum without awaiting unanimous consent.

“She championed her commitment to quality public education loudly and proudly in her famous ‘cafeteria voice,’” said Jennifer Raab, president of Hunter College, which inducted Dr. Frank into its Hall of Fame.

Ms. Frank, who made a point of reaching out to district superintendents and school principals, championed not just students but also teachers.

“We know the teachers are effective when they believe in what they are doing and feel a sense of belonging,” she told The Times in 1984. “But we also discovered other characteristics of the behavior of certain effective teachers. One was that good teachers defined the task at hand early on in the school year and explained to kids what was going to happen, as if there was then a contract between teacher and child.”

And then, she said, teachers had to be both supportive and resolved. “They had to be both sympathetic and insistent that kids learn,” she said.