San Francisco Supervisor Shamann Walton, whose district includes Bayview-Hunters Point, requested a hearing on the jury report. But his office declined repeated requests for an interview. In an emailed statement, he said he is aware of the longstanding issue of radioactive contamination and is working with all the agencies involved in the cleanup.

But he acknowledged that “the effect of sea level rise and groundwater rise has not been studied” for the Hunters Point Superfund site.

Harrison organized a June rally in front of City Hall to highlight the findings. Wearing a bright purple shirt with “CAN WE LIVE” printed on the front and speaking into a megaphone, she said the city needs to prepare Bayview-Hunters Point for the effects of sea level rise.

“I want to invite our mayor, who we love, to show us that she loves us back,” she said.

She said reparations are necessary to create an equitable future for Bayview-Hunters Point and its Black and brown residents who will be disproportionately harmed by climate change.

Government agencies redlined Black people into the neighborhood now dominated by polluting industries. As a result, residents live near toxic sites and face potentially deadly impacts from climate change.

Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai explains her map of which contaminants are found at which locations at the Hunters Point Superfund site, during a rally on February 12, 2022 in Bayview-Hunters Point. (Annelise Finney/KQED)

Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai explains her map of which contaminants are found at which locations at the Hunters Point Superfund site, during a rally on February 12, 2022 in Bayview-Hunters Point. (Annelise Finney/KQED)

“We’re tired of begging for our lives,” Harrison told KQED. “I holla for reparations because that’s paying for crimes against humanity. You can bet your bottom dollar we’re gonna need long-term care.”

California’s task force on reparations is deep in a conversation on how to repair the centuries of oppression endured by descendants of the enslaved on a statewide level. San Francisco’s African American Reparations Advisory Committee is exploring how the city can repair the harm its discriminatory policies have caused to Black homeownership, access to schools and availability of health care.

Bayview-Hunters Point residents regularly attend the meetings of San Francisco’s advisory committee to express their concerns. Lonnie Mason said at a January session that the city is not giving enough attention to the historically Black area of San Francisco. He was born and raised in the neighborhood.

“Our health risks within the community are very deep,” he said. “It goes way back. We know what time it is when it comes to Hunters Point.”

Reparations mean preparing for sea level rise

For longtime Bayview-Hunters Point residents like Tonia Randell, city leaders have taken way too long to demonstrate they value people of color in this neighborhood, one of the most polluted parts of San Francisco, according to a state environmental analysis.

“We have all the utilities here,” she said, noting the neighborhood is home to Recology; the city’s sewage treatment plant; and other waste facilities. “We still have the garbage dump here. Why is it all in our area? Because they don’t value us.”

UC Berkeley professor Maya Carrasquillo says it’s not unusual for Black people to feel left out of plans to improve residents’ lives, even if they are represented by Black city officials. Carrasquillo, who identifies racially as a Black American and ethnically as an Afro-Latina, is a civil and environmental engineering professor focused on environmental justice.

She says Black people in power would argue they advocate for all Black residents, but decisions made by those in control often center communities of affluence.

“There is still a distinct difference of how we value Black and brown lives across class barriers,” she said. “When we say ‘Black Lives Matter,’ it is all Black lives.”

Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai is documenting the toxic load in Bayview-Hunters Point residents. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai is documenting the toxic load in Bayview-Hunters Point residents. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Carrasquillo says Bayview-Hunters Point deserves the same kind of investment that wealthy neighborhoods of San Francisco receive. If that doesn’t happen, lower-income people of color will suffer disproportionately as the world warms and the bay rises. She says San Francisco and other cities should invite the people who will be the most harmed by rising tides to decide their own future by including them in every aspect of climate adaptation plans. That is an act of reparation.

“What’s actually at stake here are people’s lives,” she added. “We need to make sure that people are not at the risk of death, if we really say that their lives matter.”

‘That set my hair on fire’

To seize the attention of city leaders, residents are documenting their health conditions.

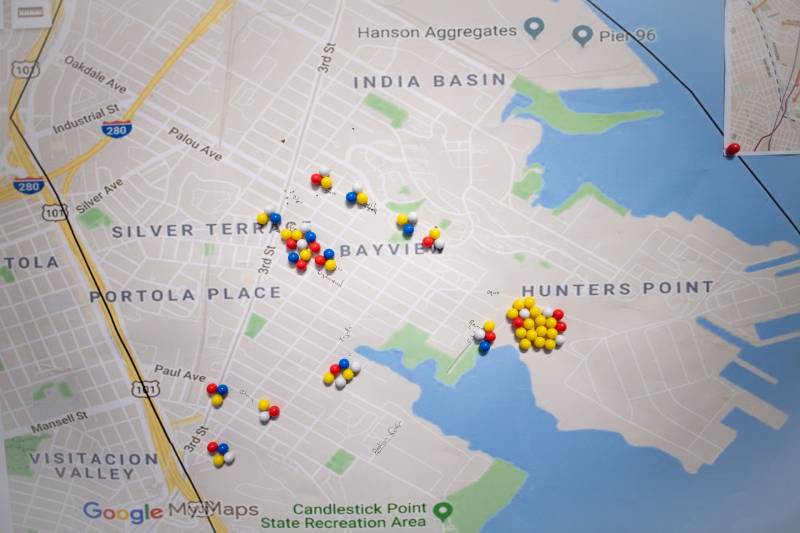

A map of Bayview-Hunters Point lies on the wood desk in Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai’s office. It’s filled with red, blue, black, yellow and white pushpins — they look like ants piled up on a piece of food. Each pin represents a person whom she tested and found to have high levels of a toxic chemical in their body at that time.

“[Toxic chemicals] have no role in the human body, and there is no justification for any of them,” she said.

Pushpins on a map show where the elements arsenic, gadolinium, manganese and vanadium were found in tests of Bayview-Hunters Point residents. Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai is conducting the urine tests and correlating the results with residents’ illnesses. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Pushpins on a map show where the elements arsenic, gadolinium, manganese and vanadium were found in tests of Bayview-Hunters Point residents. Dr. Ahimsa Porter Sumchai is conducting the urine tests and correlating the results with residents’ illnesses. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

In 2018, the state announced that a radioactive object was found near new condos in the community in an area the city and numerous government agencies said was cleaned up. For Porter Sumchai, that was the last straw.

In 2019, she began testing residents who volunteered to have their urine examined for toxic contaminants. The 70-year-old physician is the founder and medical director of the Hunters Point Biomonitoring Foundation.

She’s now tested and retested more than 100 residents for toxic elements like lead, mercury and arsenic, and for elevated levels of natural elements that people need, like iron and zinc. Porter Sumchai said she recently tested a woman in her 40s and found uranium at dangerously high levels.

“That set my hair on fire,” she said. “I had never seen anything like that.”

Harrison was tested in 2021. Porter Sumchai found cadmium, copper, manganese and other contaminants in her body at levels she described as “very dangerous.” The contaminants could cause damage to the brain, heart, kidney, liver and lungs.

“I am retaining fluid, have muscle tightness, tingling in my feet and my hair is falling out of my head like a cancer patient,” she said, pointing to the test results on her office computer. “It doesn’t look like it because my wig is really cute.”

On that day she wore long, black braids.

Officials with the San Francisco Department of Public Health told KQED in an emailed statement that the agency is “committed to protecting and promoting the health of those in the Bayview-Hunters Point” neighborhood, but wouldn’t comment directly on Porter Sumchai’s testing, saying the agency did not have a “subject matter expert.” They deferred comment to state health officials.

The results of Arieann Harrison’s tests for toxic elements her body is carrying are displayed on her computer in the Bayview on March 2, 2022. Bright red bars show high levels of lead, mercury, cadmium and thallium, among others. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

The results of Arieann Harrison’s tests for toxic elements her body is carrying are displayed on her computer in the Bayview on March 2, 2022. Bright red bars show high levels of lead, mercury, cadmium and thallium, among others. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

The California Department of Public Health told KQED in an email that it is “aware” of the community testing, but “has not been directly provided any test results from those samples.”

The city conducted a community health survey in 2006 that found “cancer is a major cause of years of life lost in Bayview Hunters Point,” and “African-American women and men have the highest mortality rates of any other racial/ethnic group for several major cancers.” But the city did not look at whether buried toxic contamination at the shipyard contributed to any health problems.

Dr. Timur Durrani, a UCSF physician who is not involved with Porter Sumchai’s effort, said the tests are cause for a wider-scale survey.

Durrani, who provides care for acutely poisoned patients at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, cautioned that to understand the full extent of the problem, a comprehensive evaluation of the exposure and the community is needed.

“What it sounds like is the community wants to be heard,” he said.

Porter Sumchai submits her data on cancers and toxic contamination to the California Cancer Registry. She is compiling her own — the Hunters Point Community Toxic Registry — and hopes to gather enough evidence documenting a relationship between illness and toxic exposure to use in a structured legal settlement.

“The more evidence we collect, the more pins we place in this map,” she said. “I do think, ultimately, there is going to be a recovery for this community. It’s just in the stars.”

But any recovery takes hard work. Porter Sumchai and Harrison’s work is practical, methodical and deliberate. Climate change adds extreme urgency to their effort.

At the June protest on the steps of City Hall, Harrison invited Porter Sumchai to speak on her findings. Rallying the crowd, she called her “a woman who has been fighting since Day One. I like to call her my second mother.”

“People in Bayview-Hunters Point are being treated like canaries in the coal mine for an impending catastrophe that will impact the entire city,” Porter Sumchai said.

Bayview-Hunters Point residents are facing a life-or-death crisis, she said, but she promised to fight, even if city leaders don’t act.

Then she quoted Marie Harrison.

“We’ll never surrender,” she said.

KQED’s Annelise Finney contributed reporting to this story.