In their application, the utility wrote that the project “represents a unique opportunity to address customer safety needs, long-term rate affordability, customer energy preference, and alignment with California’s climate goals,” in other words, a win-win-win-win.

So, people involved in the project were dumbfounded when the utility abruptly scrapped the project early this year, citing time pressure, unknown costs to address toxic asbestos in some buildings, and disagreements over how it would be financed.

PG&E representatives wrote that it was “reluctantly terminating” the project. “There remains too great a divide in parties’ perspectives on core project details that PG&E views as essential for success.”

A view of the East Campus housing development of California State University at Monterey Bay, with power lines in the background, in Marina, California, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

A view of the East Campus housing development of California State University at Monterey Bay, with power lines in the background, in Marina, California, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)  Left: A sign directs visitors to the East Campus housing office of California State University, Monterey Bay, in Marina. Right: A laundromat for residents of East Campus housing. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Left: A sign directs visitors to the East Campus housing office of California State University, Monterey Bay, in Marina. Right: A laundromat for residents of East Campus housing. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

But the turn came as a “complete surprise,” said Hayley Goodson, a managing attorney at The Utility Reform Network, one of the project stakeholders. “PG&E has been saying for years that it costs less for gas ratepayers to do the electrification project.”

Goodson said the reasons PG&E cited for dropping the project have all been known for months and argued it came down to financials.

PG&E is a heavily regulated monopoly owned by investors. One of the ways it makes a return for shareholders is on capital investments — long-lasting physical infrastructure it owns and maintains, like gas pipelines, transformers and power lines. The utility can recoup the costs of these, plus an extra percentage of that cost from their customers, which is wrapped into monthly bills.

Hayley Goodson, a managing attorney with The Utility Reform Network (TURN), poses for a portrait in the organization’s office in Oakland on Jan. 28, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Hayley Goodson, a managing attorney with The Utility Reform Network (TURN), poses for a portrait in the organization’s office in Oakland on Jan. 28, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

However, the appliances at CSU Monterey Bay would not be owned or maintained by PG&E. They would be property of the university, even though the utility would initially buy and install them.

PG&E wanted to pay for the project through its capital budget, and while some stakeholders agreed, others pushed back, asking for the costs of electric appliances to come from the utility’s operating expense budget. This would mean they would recover the costs and break even, but there would be no additional profit for shareholders.

“It’s hard not to think that PG&E just doesn’t want to do the right thing for its ratepayers if they can’t earn a profit from it,” Goodson said.

CSU Monterey Bay spokesperson Walter Ryce said PG&E notified the university it was withdrawing the application the same week it informed the California Public Utilities Commission. The project “was set to be fully funded by PG&E, and the university does not have funding to pursue a gas replacement project on its own.”

Two systems, rising costs

The idea of “pruning” the gas system is not new. Since 2018, PG&E has executed more than a hundred of these projects, ripping out old pipelines while covering the costs to electrify the homes and businesses affected.

Picture a 2-mile gas line in need of repair, winding its way to just two homes. It’s typically cheaper for PG&E, and therefore their ratepayers, if the company pays to fully electrify customers on these lines and retire rather than replace them.

PG&E is withdrawing an ambitious plan to electrify the East Campus Housing development of California State University, Monterey Bay, at a community scale, seen here in Marina, California, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

PG&E is withdrawing an ambitious plan to electrify the East Campus Housing development of California State University, Monterey Bay, at a community scale, seen here in Marina, California, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Shrinking California’s natural gas system is an objective of state regulators, as well. The CPUC published a framework to transition away from natural gas to benefit the climate and avoid spending on infrastructure that will be obsolete before the end of its useful life.

The majority of the state’s electricity, 61%, comes from sources that create no planet-warming pollution, such as renewables, hydropower, and nuclear.

The alternative to a managed transition away from gas would be a haphazard one, which would lead to higher bills for those who still use gas.

If nearly an entire street wants to go all-electric, except for just one home, utilities interpret California code to mean they must maintain the whole pipeline serving that street.

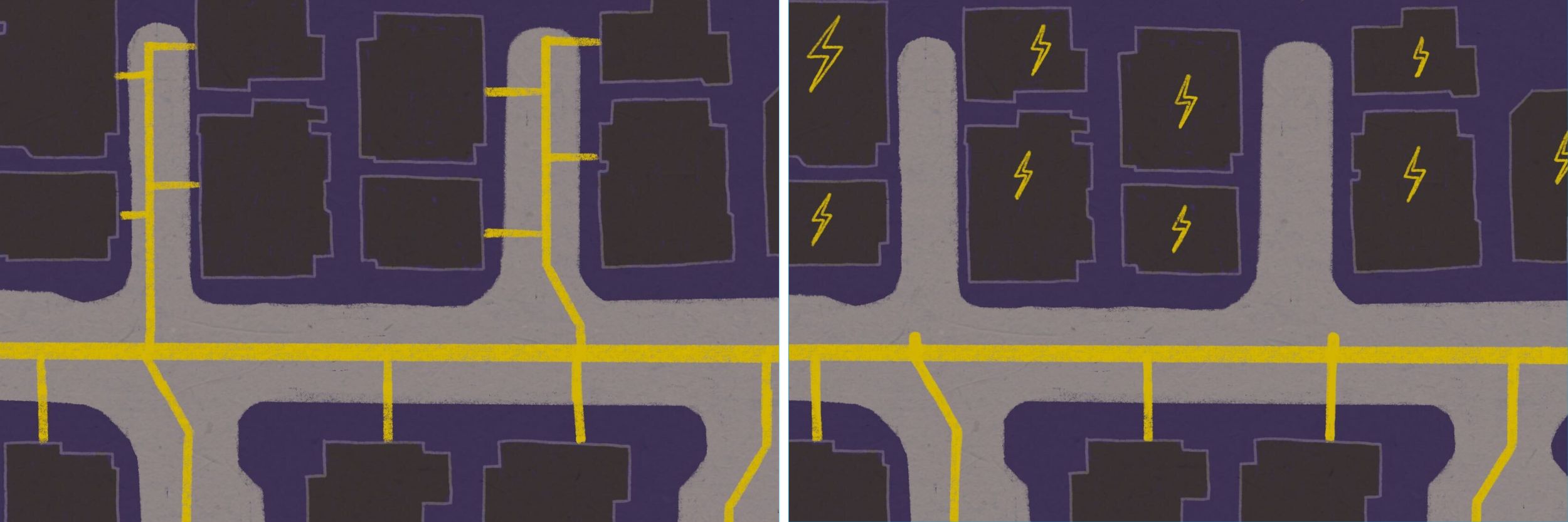

Homes and businesses powered by gas are connected through a lattice of pipelines beneath the street (left). Electrifying a neighborhood means capping a gas line and replacing the gas-fueled appliances with electric ones (right). (Anna Vignet/KQED)

Homes and businesses powered by gas are connected through a lattice of pipelines beneath the street (left). Electrifying a neighborhood means capping a gas line and replacing the gas-fueled appliances with electric ones (right). (Anna Vignet/KQED)

As more middle- and high-income people and homeowners switch to electricity, fewer people are left paying for the largely fixed costs of gas infrastructure. That leaves lower-income people and renters, who are less likely to electrify, on the hook for the cost of the gas system.

California took a small step toward addressing this issue with a law that will allow 30 communities to go all-electric with just two-thirds of residents’ consent. These are pilots, though, and will kick off in 2026 at the earliest.

A special project

The CSU Monterey Bay project would likely have saved ratepayers money.

Purchasing and installing electric appliances for roughly 400 homes saved about $2.45 million over replacing about 8 miles of gas pipelines, PG&E estimated in its project application to the CPUC.

“It’s a unicorn,” said the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Kiki Velez, who leads initiatives transitioning away from gas for the organization. “You have a big project that could likely deliver a lot of cost savings and emissions reductions. You have one willing customer.”

In a 2022 article published by the university, then Sustainability Director Lacey Raak said it made sense not to invest in gas infrastructure. “It would be like buying a fax machine in 1999,” Raak said.

The clock ticks

Time can be a major impediment when you set out to electrify a whole neighborhood.

“You want to be targeting pipelines that are close to the end of their lifetime because that’s a better deal for ratepayers,” said Beckie Menten, California director at the Building Decarbonization Coalition.

Instead of replacing them with a pipeline that may be retired before its useful, sometimes 100-year-long life, or before it’s slowly paid off, you convert the associated homes to rely on electricity instead.

Identifying a pipeline almost ready for replacement “sets a clock,” she said. “You have a certain number of years to not only get approval for the project, but to also implement the project before the safety concern becomes a risk.”

An advisory sign warns of high-voltage electricity near the East Campus housing development of California State University, Monterey Bay, in Marina, California, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

An advisory sign warns of high-voltage electricity near the East Campus housing development of California State University, Monterey Bay, in Marina, California, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2025. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

PG&E’s initial application (PDF) asked the CPUC for approval by the summer of 2023, saying the utility would need to replace the gas lines from 2022–25 to ensure future “safe, reliable gas service.” In recent filings, PG&E wrote that it’d need the pipelines replaced by the end of 2026. The utility was still waiting for a decision in early 2025.

Failing to replace aging pipelines can lead to gas leaks and cause dangerous explosions. One of PG&E’s most notorious disasters was a blast and resulting fire in San Bruno in 2010, which killed eight people. The cause was a poorly welded pipeline of a very old pipe and inadequate pipeline management.

The CSU Monterey Bay project stalled for a year after the school changed its chief financial officer. Then, campus officials found asbestos in the buildings, which could lead to health risks if disturbed during construction.

Meanwhile, project stakeholders argued over how PG&E should expense the new electric appliances.

Some stakeholders, including the Sierra Club, supported PG&E’s proposal to allow it to use capital funds and, therefore, make a profit in this case. Attorney Matt Vespa said the incentives to make climate-friendly electrification choices aren’t there yet for utilities.

“If a gas company just replaces a pipeline and basically locks in fossil fuel infrastructure for decades at a pretty high cost, they make money. But if they avoid that and do a climate solution that benefits public health, air quality and the climate by electrifying, they actually don’t make any money at all,” Vespa said.

Matt Vespa, a senior attorney with Earthjustice, sits on the counter at his home in San Francisco on Jan. 30, 2025, next to a newly installed induction stove. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Matt Vespa, a senior attorney with Earthjustice, sits on the counter at his home in San Francisco on Jan. 30, 2025, next to a newly installed induction stove. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Other groups, including TURN, scoffed at PG&E’s proposed way to finance the project and said the utility would still be able to recover its costs. “What we’re talking about is whether they should earn a bonus on these activities. We don’t think that that bonus is necessary or appropriate,” Goodson said.

A PG&E spokesperson told KQED that the utility joins “with TURN in advocating for the safe and reliable delivery of energy for PG&E customers. This includes the replacement of pipeline for safety reasons when necessary.”

The debate was not atypical for a project like this, and in December, parties were coming to agreements on issues they’d argued over. How PG&E would finance the project was unresolved and would be put to the CPUC.

But PG&E withdrew its application before it could, and with it, hopes for the largest neighborhood electrification project in the U.S. to date.