The jury “found that rising groundwater in the Shipyard could interact in dangerous ways with future infrastructure, and with hazardous toxins the Navy plans to leave buried in the soil. We wanted to know if this new science and these risks had been taken into account by the City, by OCII [the San Francisco Office of Community Infrastructure and Investment], or by the Navy and its regulators. We found that they had not.”

Jurors wrote that the city is “poorly prepared” to protect the health and safety of Bayview-Hunters Point residents, and “cannot cut corners in an era of climate change.”

For Harrison and others who live in the neighborhood around the shipyard, the report validated their message to city officials: that the threats from toxic contamination and climate change are real and demand lasting solutions.

“We want to secure the future for us as residents and for our kids,” said Harrison. “I am a mother. I am a grandmother. And I want them to not live through a legacy of toxicity. I don’t want them to worry about all the things they have to worry about in our community.”

The toxic legacy

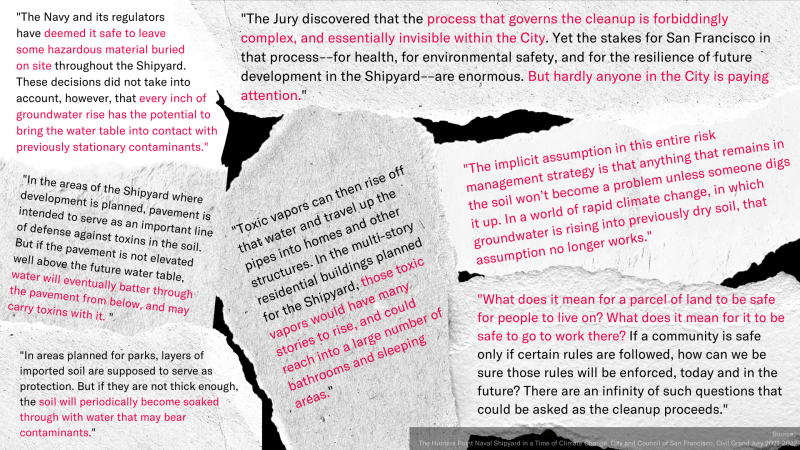

Portions of the San Francisco Civil Grand Jury report ‘Buried Problems and a Buried Process: The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in a Time of Climate Change.’ (Sarah Khalida Mohamed/KQED)

Portions of the San Francisco Civil Grand Jury report ‘Buried Problems and a Buried Process: The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in a Time of Climate Change.’ (Sarah Khalida Mohamed/KQED)

The bayshore edge of Bayview-Hunters Point is one of the most polluted areas of the entire San Francisco shoreline. The former Navy shipyard, located on the city’s southeast shoreline, is an 866-acre federal Superfund site, a location the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has designated as highly contaminated with hazardous waste.

In the middle of the last century, the Navy decontaminated ships there after atomic bomb tests and established the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory. Research and other activities contaminated the soil with radionuclides, heavy metals, and petroleum fuels, among other toxic compounds.

The Superfund site has been partially cleaned up. With the oversight of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Navy is continuing the cleanup, preparing it for the eventual development of a sweeping new neighborhood with mixed-use construction of businesses, research institutions and thousands of homes.

Scientists say the problem is that the cleanup didn’t prepare the site for the worst of rising tides. The Navy’s most recent report on the cleanup describes how, at many sites, toxic contamination that’s buried in the soil is held in place with a cap — often made of concrete, clay or strong plastic-like materials. The problem: Rising sea levels both flood on top of the land and press inward under the surface, pushing up the groundwater underneath this buried contamination.

UC Berkeley scientist Rachel Morello-Frosch says caps over toxic contamination may not hold as the bay presses groundwater upward.

“If you start having groundwater encroachment, those caps of legacy sites can be breached,” she noted. “So it can come up, and it can move to different areas.”

As groundwater rises, the buried pollution can spread throughout the community, exposing people and the bay to contaminants.

An ‘impenetrable system’

Apartment buildings in Hunters Point are seen through gantry cranes from San Francisco Bay on March 8, 2022. (Beth LeBerge/KQED)

Apartment buildings in Hunters Point are seen through gantry cranes from San Francisco Bay on March 8, 2022. (Beth LeBerge/KQED)

The grand jury report is an indictment of the city and the regulatory agencies overseeing what happens at the Hunters Point Superfund site — that is, the Navy, the federal Environmental Protection Agency, the California Department of Toxic Substances Control, and the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board.

The report says lack of attention, inaccessible documents, technical language and poor communication among the agencies involved in cleanup at the Superfund site leave residents of Bayview-Hunters Point and the city unacceptably vulnerable to contamination.

The San Francisco Civil Grand Jury is a panel of 19 citizens who don’t work in government. They serve for a year to investigate and issue reports on significant local government actions or, as they make clear in this case, government lack of action.