And for the scientists working up here in 2025, the job is essentially “to play in the snow and learn more about it,” said Andrew Schwartz, its director.

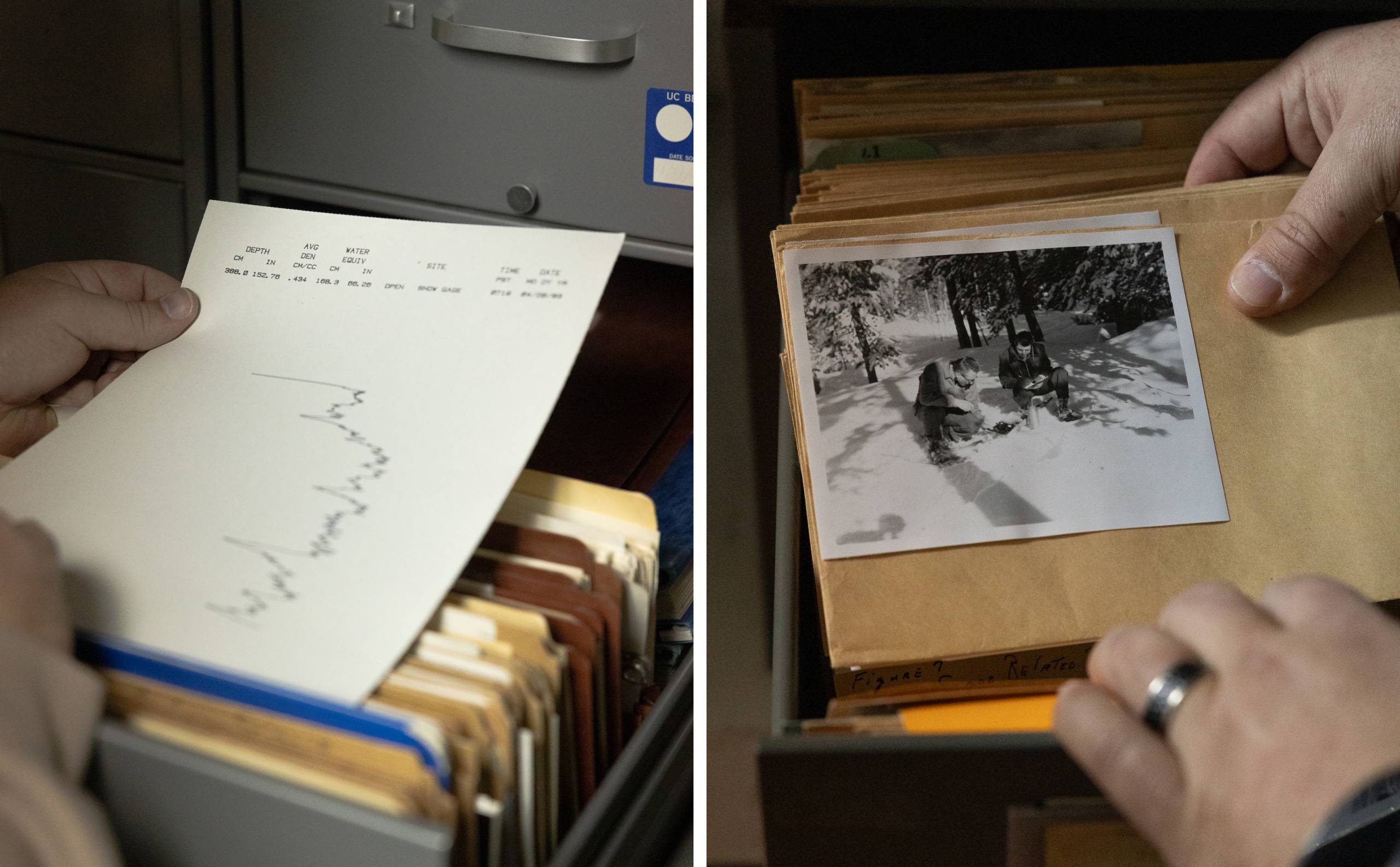

Andrew Schwartz, director of UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab, holds a decades-old printout of snow measurements (left) and a black-and-white photograph (right) in the lab’s archives. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Andrew Schwartz, director of UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab, holds a decades-old printout of snow measurements (left) and a black-and-white photograph (right) in the lab’s archives. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

For the three days in January that saw 20 students from across the U.S. arrive at the Snow Science School, Tahoe was in the middle of a sunny, dry spell, with the snowpack at Donner Summit at 94% of the average for this time of year. But at an elevation of over 6,700 feet, the Snow Lab has seen its share of wild winters and momentous snowfall — making it an apt place to study snow science any time.

Schwartz, who took over the Snow Lab in 2021 and lived inside the building for his first two years, recalled how, in 2023, the snow was so deep that he and his colleagues could “walk directly into the third-floor windows.” That year, the Snow Lab received a total of 63 feet of snow, its second-biggest winter accumulation on record — precipitation that would eventually become the snowmelt that’s crucial for California’s water supply.

Participants listen during a morning lecture at the Clair Tappan Lodge during the Snow Science School organized by UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Participants listen during a morning lecture at the Clair Tappan Lodge during the Snow Science School organized by UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

For Schwartz, his “number one” hope for the Snow Lab’s inaugural school is that the students leave “with an appreciation of snow and a better understanding of how it works, really — because it’s so important to the world.”

“Roughly two billion people [around the world] use water obtained from snowpack. And we tend to take it for granted,” he said.

The school’s student body included a large handful of people from the California Department of Water Resources — one of the Snow Lab’s partners in this work — but also graduate students, researchers, snow modelers and teachers, as well as folks sent by the National Parks Service and the National Forest Service.

Participants gather for a morning lecture during Snow Science School. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Participants gather for a morning lecture during Snow Science School. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

The breadth of experience and background among the Snow Science School’s students is a testimony to the wide range of applications this work can have — and to the disciplines that snow brings together. “It’s a very close-knit community,” said Preetika Kaur, a Snow Lab student attending from the University of Wyoming. “I love to meet people who are pros.”

All work and no play? Not at the Snow Lab

After climbing up the steep hill to the Snow Lab on their first day, students were shown past the bright red snowcat — the exact same model that’s featured in the movie The Shining, noted Schwartz approvingly — and into the warren-like building. Above their heads, the top floor holds sleeping quarters for the scientists who board overnight to conduct research or who’ve been trapped inside by an impenetrable Sierra storm.

UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab, based in Soda Springs near Donner Summit. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab, based in Soda Springs near Donner Summit. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

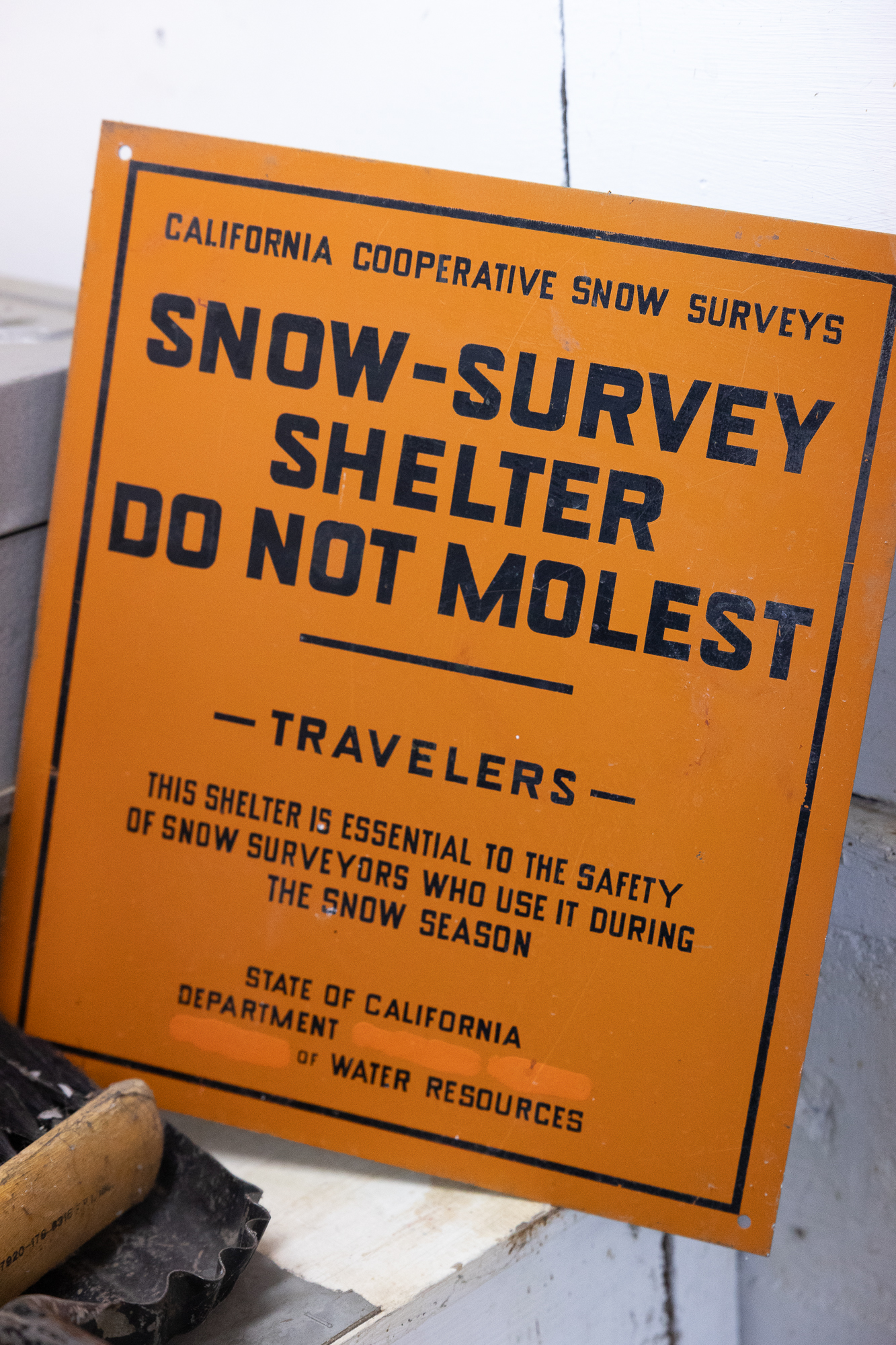

The first floor and basement, where the lab’s scientists work throughout the day, was full not just of computer screens and boxes full of measuring tools but also handwritten logs, archive photography depicting their Snow Lab predecessors out on the job, vintage road signs and instruments saved from the building’s past.

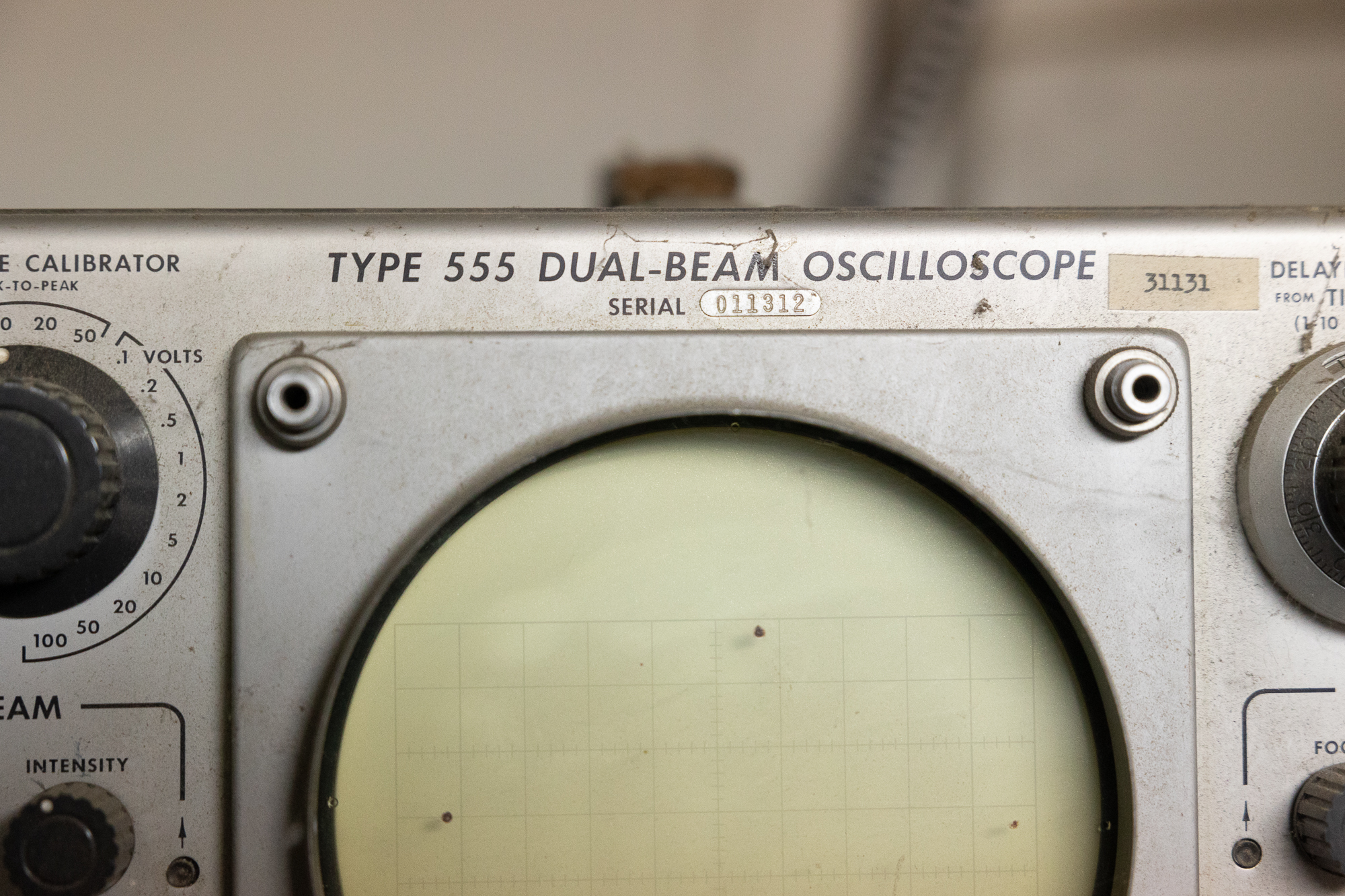

There’s even an oscilloscope — an instrument that once measured voltage — with a large “NASA AMES” sticker on it, and even though Schwartz admits they “have no clue” what the Snow Lab scientists of previous years used it for up here, “I’d be lying if I still don’t like to play with the knobs on it,” he said.

A Type 555 Dual-beam Oscilloscope, circa 1960s, at the Central Sierra Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

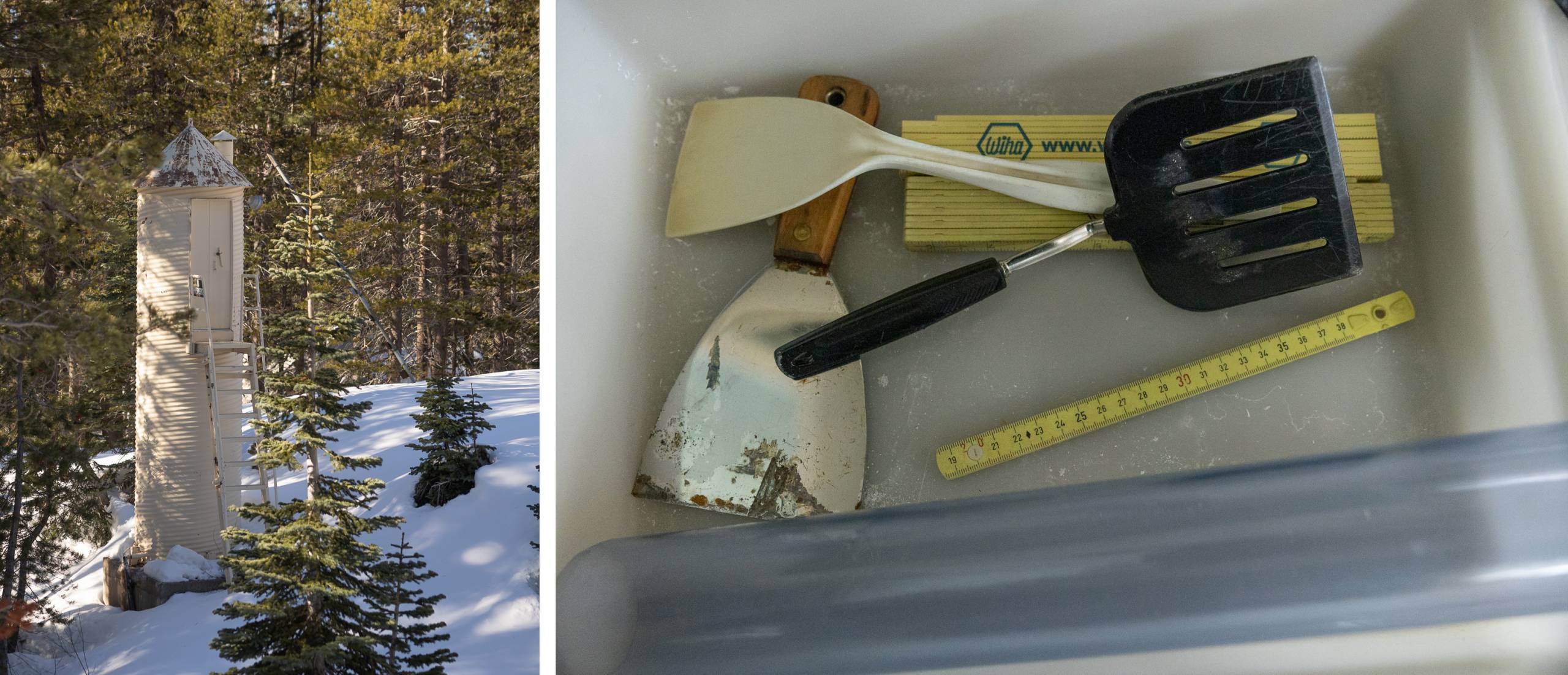

A Type 555 Dual-beam Oscilloscope, circa 1960s, at the Central Sierra Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)  Spatulas and rulers (right) are some of the tools used to measure snowfall at the Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Spatulas and rulers (right) are some of the tools used to measure snowfall at the Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Outside, the students tour Snow Lab’s network of remote snow equipment, like the fluid-filled “snow pillow” that detects the weight of the snow falling on it and the sensors submerged in the creek behind the lab that will gauge the height of the icy water as it starts to rise with spring snowmelt. Other remote sensors constantly assess solar radiation — in a region where sunlight can contribute to up to 95% of snowmelt — and soil temperature to get an idea of just how fast the snowpack could melt this year.

But as this data collection hums in the background, Schwartz still maintains the lab’s twice-daily manual measurement tradition, which sees him and his colleagues crunch out onto the snow with “our very fancy ruler” — work that on some days, depending on conditions, can feel more like a polar expedition.

Gaby May Lagunes, a Ph.D. student in the Environmental Science, Policy, and Management Department at UC Berkeley, puts on her snowshoes to head into the field. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Gaby May Lagunes, a Ph.D. student in the Environmental Science, Policy, and Management Department at UC Berkeley, puts on her snowshoes to head into the field. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

As the Snow Lab’s social media presence has gained in popularity in the last few years, the snow measurements that Schwartz and his team make public are also watched eagerly by a different group of California enthusiasts: skiers and snowboarders desperate to know when to hit the Tahoe slopes.

“I love the different uses of our data in our information,” he said.

The impact of the snowpack on water supply

The snowpack can contain clues of the past as well as the future — which is why the snow analysis techniques being taught at the Snow Science School go way beyond just assessing depth.

A key concept hydrology students are taught about is “snow water equivalent,” or SWE (usually pronounced “swee” by snow scientists): A measurement that tells scientists just how much water is contained in an area of snow versus the air it also contains alongside its ice crystals.

Andrew Schwartz, right, director of the Central Sierra Snow Lab, leads instructors and participants of the Snow Science School into the field. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Andrew Schwartz, right, director of the Central Sierra Snow Lab, leads instructors and participants of the Snow Science School into the field. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

“A lot of the water in California originally falls as snow, and it’s really valuable to humans because there’s a lot of it and because it stores itself for free in places where it’s cold and then melts in the spring, which is when we need it for agriculture,” said Marianne Cowherd, research associate at the Snow Lab and one of the instructors. “Having a good understanding of how much water we have available upstream lets us do things like manage our reservoir levels — so we still have enough water, but we don’t have dangerous operations or overflow.”

The next piece of the snow science puzzle is working out when and how the state can expect that snow to melt. At the school, the students learn more about how energy from the sun and from the warm temperatures of the air and from the ground melts the snowpack and how the water flows into California’s soils and streams.

“The thing that I’m trying to do is understand the effect of human changes in the landscape, specifically with irrigation on future precipitation patterns and precipitation extremes,” said Gaby May Lagunes, a snow lab student and UC Berkeley graduate researcher. “How the way people change the environment has an impact on the water cycle, not only locally, regionally and globally.”

So “if I want to understand water from a data-driven perspective, I need to have an idea of what snow people know,” she said. “We need to work together a lot because we cannot know everything.”

Preetika Kaur, left, a Ph.D. student at the University of Wyoming, and Joe Ammatelli, an assistant research scientist with the Desert Research Institute, dig a pit in the snowpack during Snow Science School. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Preetika Kaur, left, a Ph.D. student at the University of Wyoming, and Joe Ammatelli, an assistant research scientist with the Desert Research Institute, dig a pit in the snowpack during Snow Science School. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Up close in the snow pits

For students, the real action came when the school decamped closer to Donner Summit for the field measurement portion of their studies. After suiting up in thermal layers, bibs and beanies — plus lab-supplied polarized sunglasses that read “No Biz Like Snow Biz” on the side — the students strap on snowshoes to make the hike along a snow-covered trail to a secluded woods, sandwiched between Sugar Bowl and Donner Ski Ranch. Here, they began to dig out a series of 4-foot-deep snow pits using shovels, low enough to strike soil and complete with steps.

The snowpack can be far larger, sometimes as deep as 20 feet, and scientists “have to build literal levels down to measure the whole thing,” Schwartz said — “so you don’t have to Spider-Man your way out every time.”

Joe Ammatelli was sent by the Desert Research Institute in Nevada, where he carries out snow modeling, which needs to be validated by field observations. “It’s really valuable as a modeler to get out here and see how it’s done,” he said.

Snow crystals lay on a measuring device during a field outing with the Snow Science School in January. Chris Northart, right, with the Department of Water Resources Statewide Monitoring Network Unit and a participant of the Snow Science School, uses a magnification lens to measure the size of snow granules. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

Snow crystals lay on a measuring device during a field outing with the Snow Science School in January. Chris Northart, right, with the Department of Water Resources Statewide Monitoring Network Unit and a participant of the Snow Science School, uses a magnification lens to measure the size of snow granules. (David M. Barreda/KQED)  A participant of the Snow School weighs a wedge of snow collected from the snowpack in a field outing. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

A participant of the Snow School weighs a wedge of snow collected from the snowpack in a field outing. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

And for all the technological developments in snow science, it remains deeply tactile for its practitioners. Down in the pits, the students measured the snow’s temperature and observed how it changed the deeper the pit went. Then, using specialized shovels, the students scooped out and leveled off snow before weighing it on a scale — a method of measuring density and snow water equivalent.

They examined physical changes in the different layers in the smooth white walls of the snow pits, like studying rings in a tree trunk. These kinds of measurements are an exercise in time travel, explained instructor Cowherd, given the different qualities of snowflakes that fall at different times and how the ever-accumulating snowpack ages.

As the air heats and cools, the snow melts and compresses under its own weight — all of which “tells us about the history of what’s happened there,” Cowherd said.

‘Every day in the snow is a good day’

The observations that the instructors taught its snow students in the pits are the kind that stretches back almost a century and a half in the Snow Lab’s own archives — and this volume of information is invaluable for assessing the impact of climate change, Schwartz said.

“We see the same amount of precipitation coming in, but it’s shifting from snow terrain in all the months — so we’re seeing warming,” he said. “Our rain-snow line is going up in elevation.”

The almost 150 years of data can also aid forecasters in looking for variables that smaller data sets just can’t encompass, he said — like the Sierra’s dry spells that are followed by big years for rain and snowfall, a swing that’s seen in “five year periods.”

A sign to alert the public of a snow survey shelter structure from the Department of Water Resources is one of the objects in the archive at the Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

A sign to alert the public of a snow survey shelter structure from the Department of Water Resources is one of the objects in the archive at the Snow Lab. (David M. Barreda/KQED)

The school’s emphasis on continuing the tradition of meticulous data collection is shot through with the deep enthusiasm that marks the people in its orbit. Even in the chill of the field, when digging out feet of snow, the students remain upbeat.

“Snow people are really fun people for the most part,” said instructor Micah Johnson, as he demonstrated an invention he’d been working on for a decade — showing the students how to stab his Bluetooth-enabled “penetrometer-reflectometer” stick into the snow and call up data from its sensors. “I have yet to meet an indifferent snow scientist of sorts.”

Or, as Ammatelli from the Desert Research Institute said, “Every day in the snow is a good day.”