The Geminids shower typically produces around 120 meteors per hour, so under clear, dark sky conditions, you may see up to two a minute.

At 2 a.m., Gemini will be almost directly overhead, easily identified by its two equally bright stars, Castor and Pollux, the twin brothers of Greek myth. Meteors may be seen almost anywhere in the sky, but if you lie down on a blanket and lock your gaze onto Gemini above, you’ll maximize the number of falling stars you can catch.

This year the waning gibbous moon, which is a not-quite-full moon diminishing toward the third-quarter phase, will rise around 10 p.m. on Tuesday evening and remain in the sky until well after dawn. Still, the Geminids shower tends to produce bright meteors that will be visible despite interference from moonlight.

Where can you find the darkest skies?

The best place to watch a meteor shower is where skies are darkest, away from urban lights. If you live in the city, light pollution can be difficult to avoid, and driving miles from home in the middle of the night can be an undertaking of planning and willpower. But the rewards are well worth it.

You might see a meteor or two even from a city dwelling, but the Bay Area has numerous places you can reach in less than half an hour that provide some protection from city lights.

Composite image of the telescope domes at Chabot Space and Science Center under the clear night sky. (Chabot Space and Science Center/Conrad Jung)

Composite image of the telescope domes at Chabot Space and Science Center under the clear night sky. (Chabot Space and Science Center/Conrad Jung)

In the South Bay, Henry Coe State Park is a prime spot. Along the peninsula are dark niches bordering the coastal mountains. North of the bay, in Sonoma and Napa counties, are wide spans of dark country roads to choose from. In the East Bay hills are some good pullouts, from the Tilden Park region all the way south to Sunol. Mount Diablo offers some good spots, as well.

In any case, you know your home ground best and probably can think of some good spots. Be wise, be safe and dress for the cold.

What is a meteor shower?

A meteor is a small bit of space rock or metal, typically no bigger than a pebble, that burns up when it enters Earth’s atmosphere traveling at speeds of many miles per second. You’d get pretty hot, too, going that fast through the atmosphere — ask any astronaut who has been to space and returned home in a fiery reentry.

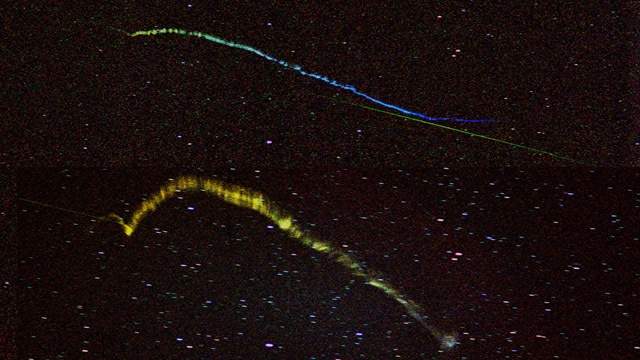

Luminous and colorful streaks left behind by shooting stars of the Leonids meteor shower, which takes place annually in November. Color in meteors comes from different composition of the dust grains burning up. Some are composed of stone, others of metal. (Chabot Space and Science Center/Carter Roberts)

Luminous and colorful streaks left behind by shooting stars of the Leonids meteor shower, which takes place annually in November. Color in meteors comes from different composition of the dust grains burning up. Some are composed of stone, others of metal. (Chabot Space and Science Center/Carter Roberts)

A meteor shower happens when Earth passes through a cloud of dust left behind by the passage of a comet. When Earth slams into the dust cloud, moving along its orbit around the sun at 18 miles per second, its sky becomes filled with the incinerating specks: meteors.

Meteor showers are best viewed in the early morning hours because the viewer is on the side of the Earth moving into the dust. Think of a car speeding along a freeway and driving through a cloud of flying insects: Bug streaks only appear on the windshield and not the rear window.

Where did the Geminids shower come from?

The Geminids meteor shower is unusual for another reason. While most showers come from trails of dust left behind by comets that passed through the inner solar system, the Geminids originate from what astronomers call a “rock comet” named 3200 Phaeton.

Radio telescope image of 3200 Phaeton, the ‘rock comet’ that is the source of dust that produces the Geminids meteor shower. (Arecibo Observatory/NASA)

Radio telescope image of 3200 Phaeton, the ‘rock comet’ that is the source of dust that produces the Geminids meteor shower. (Arecibo Observatory/NASA)

Unlike typical comets that are made mostly of frozen water and other volatile materials, Phaeton is more like an asteroid, composed of rock and dust and probably some ice as well. When it passes close to the sun, Phaeton heats up, and some of the ice it contains vaporizes, blowing off into space and carrying dust with it.

For your added viewing enjoyment

As long as you’re up so early waiting to see meteors, take the time to look around at some of the sky’s other wonders.

First, the moon is up there. Enough said.

The planet Mars shines high in the sky to the west of Gemini. To locate this rosy celestial gem, look for a bright orange dot shining steadily, without flickering like stars do. Stars flicker because they are distant enough to be simple delicate points of light, strongly affected by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere, like candles blowing in the wind. Planets, however, are much closer and appear in the sky as disks, much less influenced by atmospheric refraction.

And you can’t miss the complex of bright stars that form Orion and his famous belt of three.

Spanning the sky to the south of Gemini is the asterism called the Winter Triangle, formed by the bright orange star Betelgeuse in Orion, the golden-white Procyon, and the brightest star of the night sky, the rainbow sparkler Sirius.