Most teachers have at least one or two students with IEPs in their classrooms each year, and sometimes many more. What is an IEP, and how does it affect students, teachers, and families? Here’s what you need to know.

What is an IEP?

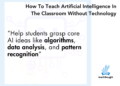

Source: Modern Teacher

IEP stands for Individualized Education Program. It’s a legal document that clearly defines how a school plans to meet a child’s unique educational needs that result from a disability. IEPs were first introduced in 1975, when Congress passed legislation that gave children with disabilities the right to attend public schools.

Today, IEPs are covered under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). This federal law entitles all children with certain types of disabilities a free, appropriate education. Children who qualify must be provided with an education that meets their unique needs, provides access to the general education curriculum, and meets state grade-level standards.

What is the purpose of an IEP?

The IEP is the cornerstone of a child’s special education program. It assesses their present performance, sets reasonable measurable goals for the child, and specifies the services the school will provide. IEPs grow and change along with a child and are regularly reevaluated to ensure they’re still effective (at least annually, sometimes more frequently).

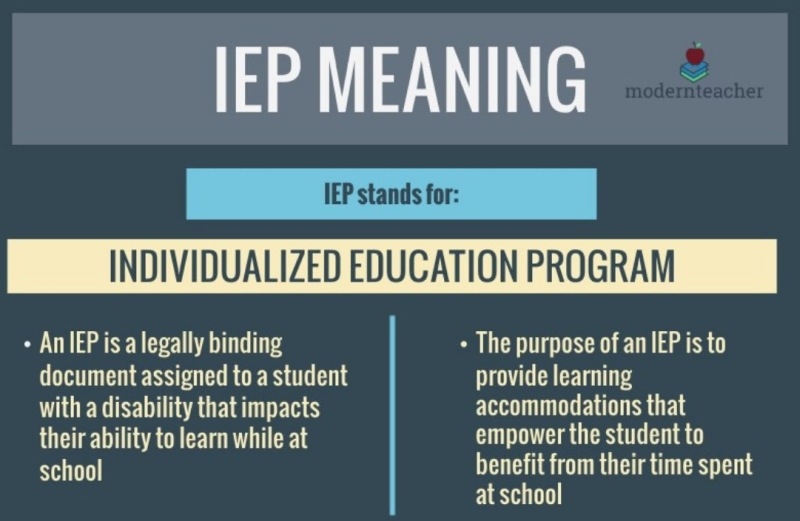

IDEA says that school districts must provide a free, appropriate public education (FAPE) to all children. What’s more, they must allow students to participate in that education in the least restrictive environment (LRE) possible. They must be given the opportunity to participate in the traditional school experience to the full extent possible.

Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)

Source: LREs at Undivided

When federal law first required public schools to admit special education students in the 1970s, many of them grouped these students together into special ed classrooms or buildings. This isolated them from their peers, leading to stigma among the general public. Plus, students of wildly varying abilities were often all in one classroom, making it difficult to meet all of their needs.

When IDEA went into effect in 1990, one goal was to change the stigma and give all students a more appropriate education among their peers. To that end, the law stated students must learn in the least restrictive environment. In other words, schools were urged to find ways to serve students with special needs in the general classroom whenever possible.

An IEP can help schools and teachers figure out how to help students succeed in the LRE that’s right for them, which for many is a general education inclusion classroom, possibly with push-in, pull-out services. For some students, a general classroom isn’t an appropriate LRE. However, the law requires schools to do their best to keep kids learning alongside their peers before opting for a different choice.

Learn more about Least Restrictive Environments (LRE) here.

Who qualifies for an IEP?

IDEA covers children from birth until they graduate high school or turn 21, whichever comes first. To qualify, a child must fall under one of 13 disability categories, and their disability must adversely affect their school performance. Just because a child has a disability does not mean they need special services or require an IEP. They do have the right to be evaluated for one, though.

These are the included categories and legal definitions under IDEA:

- Autism Spectrum Disorder: A developmental disability that mainly affects a child’s social and communication skills, and sometimes behavior

- Deafness: A severe hearing impairment that prevents a child from processing language through hearing

- Deaf-Blindness: A combination of a hearing and a visual impairment

- Hearing Impairment: Hearing loss that is less severe than deafness

- Intellectual Disability: Below-average intellectual ability

- Multiple Disabilities: A child with more than one condition covered by IDEA

- Orthopedic Impairment: An impairment to a child’s body, no matter the cause

- Other Health Impairment: Conditions that limit a child’s strength, energy, or alertness

- Specific Learning Disability: A learning issue that affects a child’s ability to write, listen, speak, reason, or do math

- Speech or Language Impairment: A range of communication problems such as stuttering, impaired articulation, etc.

- Traumatic Brain Injury: A brain injury caused by an accident or some kind of physical force

- Visual Impairment, including Blindness: Partial or complete loss of sight, not correctable by eyewear

What information does an IEP include?

Each IEP must be an individualized document, created especially for the child in question. There is no standard form, but the law does require it to include sections for present levels of performance, goals, and services. See a sample IEP with its sections explained here.

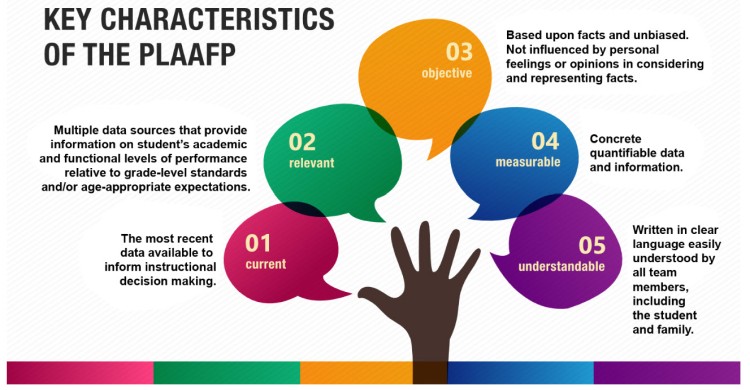

Present Levels of Performance (PLOP, PLP, or PLAAFP)

Source: Maryland Online IEP

This section documents a child’s current school performance and how their disability affects their progress and involvement. These are reevaluated on a regular basis, at least annually, and updated as needed. They should include a detailed look at:

- Academic Achievement: This refers to a child’s progress in academic subjects like reading, math, science, etc. It could be based on observations of classroom teachers, grades, results of state and district standardized tests, special education evaluations, and more.

- Functional Performance: This term encompasses all the skills and activities kids learn that aren’t directly related to academics. That might include language development, social skills, behavior, life skills, mobility skills, and so on.

Learn more about the Present Level of Performance component of an IEP here.

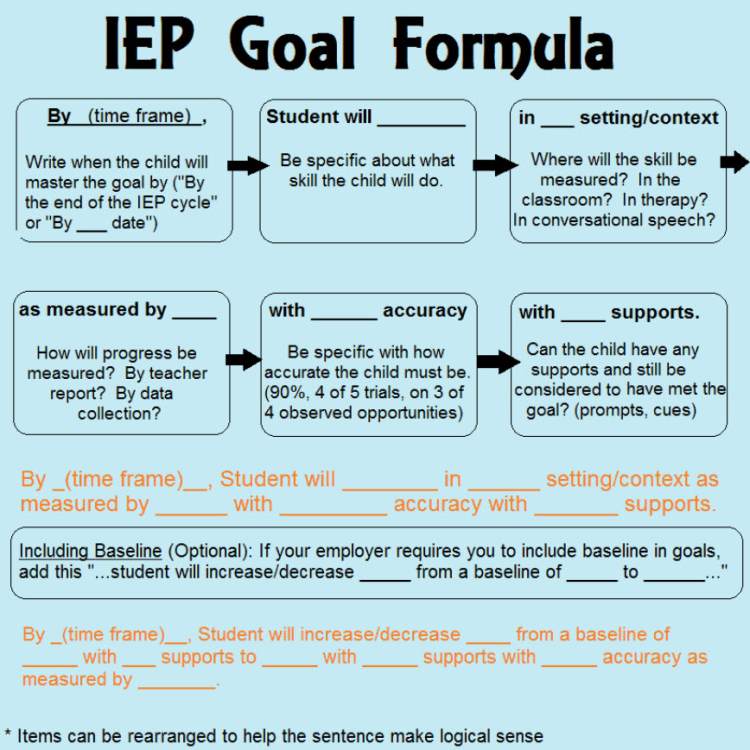

Goals

Source: A Day in Our Shoes

An IEP must include measurable goals for the student that can be reasonably accomplished in a school year. The goals are based on the student’s present level of performance and focus on the student’s specific needs.

It’s vital that the goals on an IEP be “measurable.” This means they must be very specific in their wording. A goal should include how success will be measured, and when progress is expected to be seen.

Here’s an example of a poorly written IEP goal: “The student will improve their reading skills by focusing on sight words.” This goal doesn’t include any way in which progress can be measured, or a projected time frame for meeting the goal.

Instead, this goal might say, “At the end of the first grading period, the student will demonstrate mastery of a list of 50 common sight words by reading aloud the words when presented on flash cards, with an accuracy of 95%.”

Discover much more about IEP goals here.

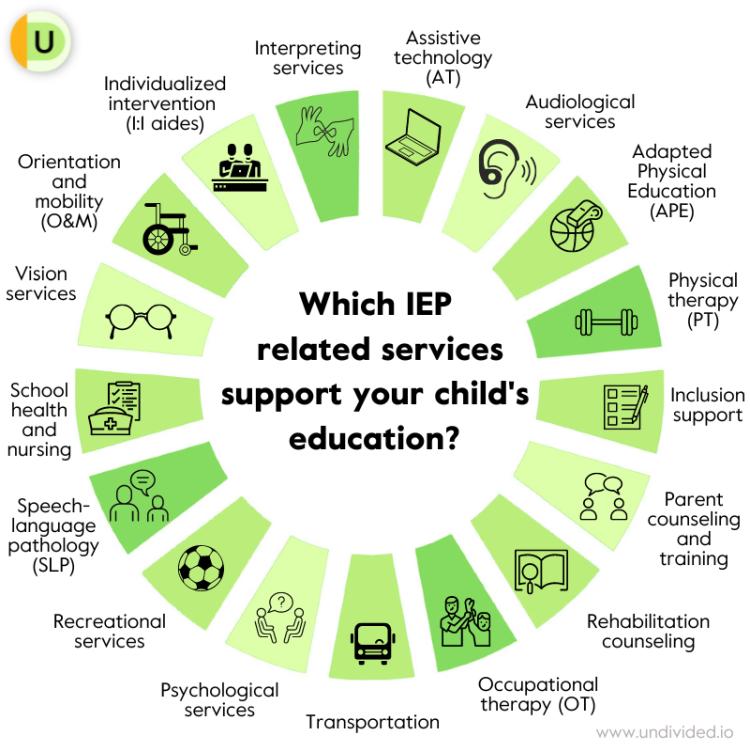

Services

Source: IEP Related Services at Undivided

In this section, schools state the ways they’ll help the child achieve their IEP goals. This might include:

- Accommodations: These are special arrangements that aren’t part of the standard classroom equipment or policy. For instance, a child with sensory-processing issues might be permitted to wear noise-cancelling headphones in the classroom. Or a student with vision challenges might have a written test read aloud to them and be allowed to respond orally. Accommodations don’t change what a student learns, it only changes how they learn it. See more examples of classroom accommodations here.

- Modifications: Modifications do involve changes to what a child is learning. They might lower or raise expectations for specific standards, or reduce the amount of work a child is expected to produce. Learn about modifications vs. accommodations here.

- Assistive Technology: Examples include text-to-speech software, typing instead of handwriting, closed-captioning, hearing aids, pencil grips, etc. See more about assistive technology here.

- Related Services: These are any other services kids need to help them succeed in the LRE, such as transportation services, occupational therapy, social skills groups, interpreters, or classroom aides. Here’s more on IEP related services.

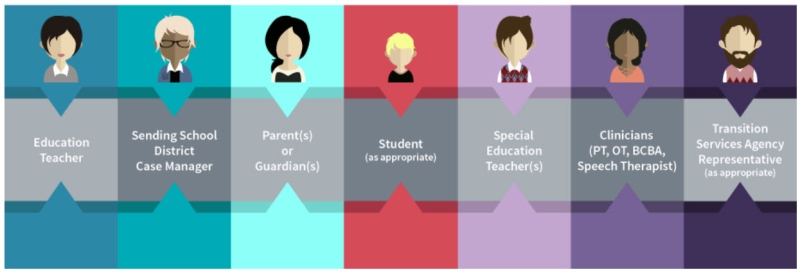

Who creates an IEP?

Source: FosterVA

Under IDEA, schools are required to actively seek out and identify students who qualify for special education services. It’s often a classroom teacher who first suggests a student be evaluated for these services. Other times, a doctor, counselor, or parent may initiate the process.

Once a school decides to evaluate a student, they must seek parental approval. Schools usually have set processes in place, including assessments and evaluations, but they must follow the law. Most districts have IEP coordinators to help with the process. Parents may also choose to have their children evaluated privately, at their own cost.

After an evaluation determines a child qualifies for special education services, the IEP team is assembled. This might include:

- Classroom teachers

- Special ed team members

- Counselors or psychologists

- Behavioral specialists

- District representatives

- Other interested parties, such as other teachers or staff members who interact with the child

- Parents or legal guardians

- Child, if appropriate

The IEP team changes over time, and not all members must attend meetings. However, at each formal yearly evaluation, it’s best to assemble as many members of a team as possible.

What rights do parents have in the IEP process?

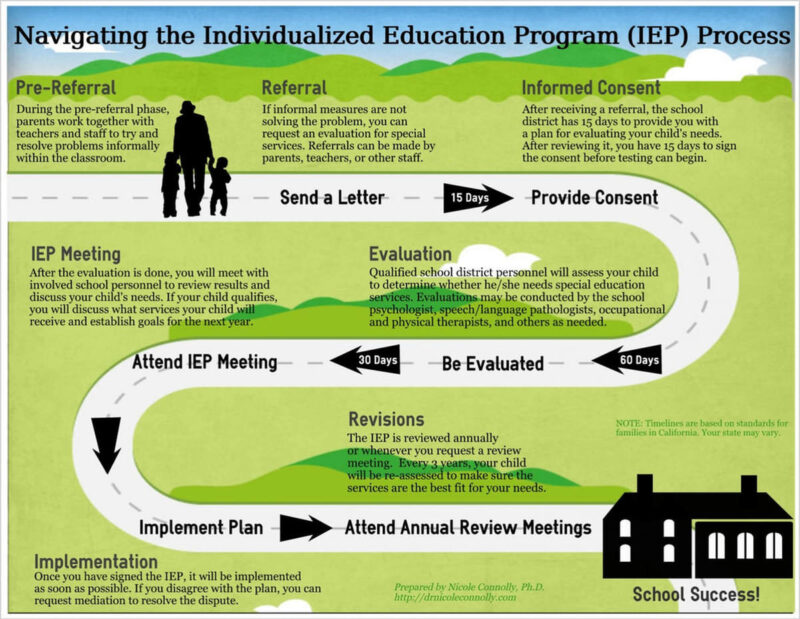

Source: Dr. Nicole Connolly

The law gives parents some very specific rights in the IEP process. Parents and legal guardians have the right to:

- Request a special education evaluation at no cost

- Give or deny consent for a special education evaluation

- Agree or refuse the special education services offered

- Have an independent evaluation performed (at their own cost)

- Disagree with a school’s decision by asking for a due-process hearing or mediation

- Participate in or request IEP meetings, and bring others to the meeting

- Review IEP documents at any time

- Control who has access to their child’s IEP

- Receive prior written notice of any proposed changes to the IEP

Find out more about IEPs and parental rights here.

IEP Resources

In addition to the resource links throughout this post, here are some additional places to find info for parents, teachers, and schools on IEPs.

Have more questions about IEPs? Come ask for advice in the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Also check out What Is a 504 Plan?