The annual Perseids meteor shower in August is one of the best and most reliable shooting star shows of the year.

The Perseids will reach their peak of activity in the early morning on Saturday, August 13. In the hours leading up to dawn, you could see as many as 50 meteors per hour – almost one a minute – with clear, dark viewing conditions.

The full moon will be in the sky all night and moonlight will challenge you to see fainter Perseids, but the brighter ones will still be easy to spot.

Where do I look?

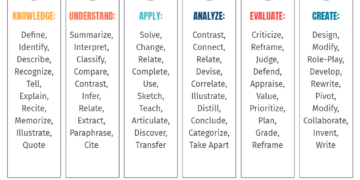

After midnight, looking to the northeast will face you toward the Perseids’ “radiant point,” the spot in the sky they will streak from. This is in the constellation Perseus, the shower’s namesake.

A view of how the northeastern sky will look at 2:00 a.m. on the morning of August 12, featuring the location of the constellation Perseus and the radiant point of the Perseids meteor shower. Mars will shine bright in the east as well. (Ben Burress – chart made using Stellarium)

A view of how the northeastern sky will look at 2:00 a.m. on the morning of August 12, featuring the location of the constellation Perseus and the radiant point of the Perseids meteor shower. Mars will shine bright in the east as well. (Ben Burress – chart made using Stellarium)

Find a good viewing location with a dark sky and a clear view to the east, free of obstructions like hills, trees and buildings. Get comfortable and watch the sky.

Though the meteors will radiate from the vicinity of Perseus, they can flash across any part of the sky. You never know when or where one will appear, so set your sights on the entire scene, just like you would watch a big-screen action film you haven’t seen before.

Where do I go to see them?

You can see the Perseids shower from anywhere with an unobstructed view of the sky, even your own backyard. If you live in a city, the number of falling stars you might catch will be limited by the height of obstacles around you and by light pollution from streetlights, buildings, and cars – so it helps to get away from that if possible.

A Perseids meteor caught in the skies of West Virginia in 2016. (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

A Perseids meteor caught in the skies of West Virginia in 2016. (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Fortunately there are places around the Bay where you can find relatively dark skies if you’re willing to travel a bit. These include Henry Coe State Park in the south bay, Mount Diablo in the east, just about anywhere in the north bay area, and along Skyline Boulevard on the peninsula.

Chabot Space & Science Center is holding a meteor watching party on its observatory deck, weather permitting.

Stay safe, check the weather forecast for clear skies, and dress appropriately.

What causes meteor showers?

A meteor is a small speck of rock or metal that strikes Earth’s atmosphere at speeds measured in tens of miles per second. Friction with the atmosphere quickly heats the pebble-sized grain and it vaporizes in a flash, leaving a brilliant streak behind. Most meteors burn up 40 or 50 miles above Earth’s surface, so those luminous trails can be dozens of miles long.

Astronaut Ron Garan took this image from the International Space Station, featuring a Perseids meteor burning up in Earth’s atmosphere as seen from space. (NASA/Ron Garan)

Astronaut Ron Garan took this image from the International Space Station, featuring a Perseids meteor burning up in Earth’s atmosphere as seen from space. (NASA/Ron Garan)

A meteor shower happens when Earth moves through a cloud of dust left behind by a comet that flew by the sun at some time in the past. When a comet passes close to the sun, solar heating vaporizes ice on the comet’s surface, which then blows off into space to form the familiar comet tail.

The comet also sheds dust embedded in its ices, leaving behind a trail. Each year when Earth returns to the same point in its orbit, we pass through the dust trail and enjoy the fiery demise of meteors. Meteor showers are visible in the morning hours because that’s when we’re on the side of the Earth plowing into the dust – kind of like how we only see bugs hit the windshield of a car and not the rear window.

Each different meteor shower throughout the year comes from the dust trail of a different comet.

The Perseids’ parent comet is named Swift-Tuttle, discovered in 1862 independently by Lewis Swift and Horace Parnell Tuttle.

Swift-Tuttle orbits the sun once every 133 years, and last passed by Earth’s neighborhood in the solar system in 1992.